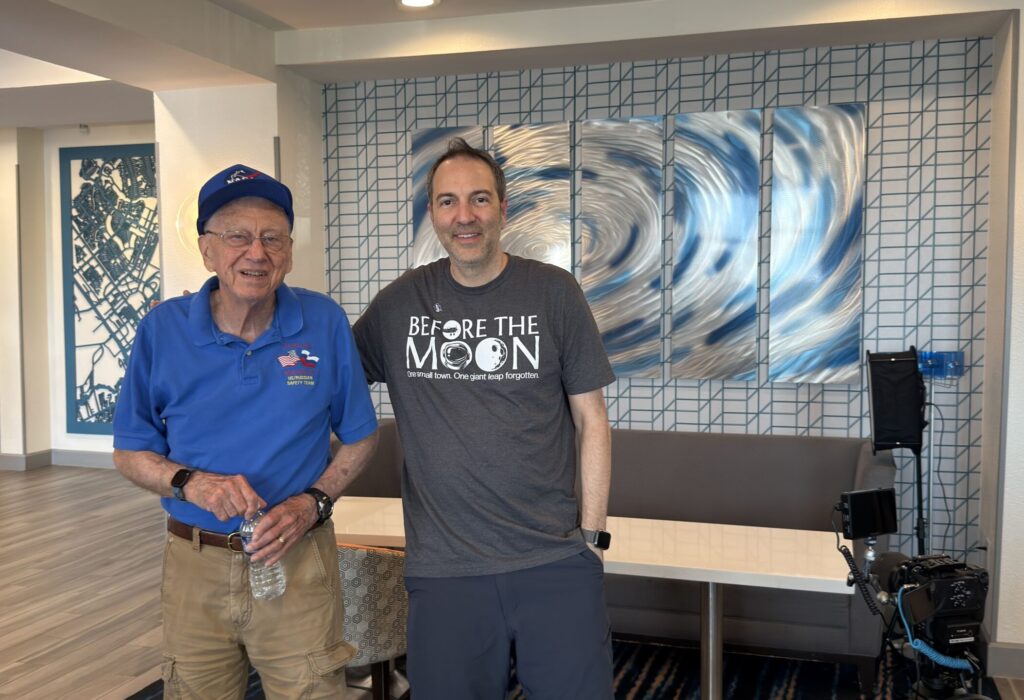

In June 1964, a young engineer named Gary Wayne Johnson packed his wife, their belongings, and their dreams into a VW Bug and drove to Houston. “That was about all we owned,” he laughed. “I’d just graduated from Oklahoma State. I changed my major from chemical to electrical engineering because I wanted to work in the space program.”

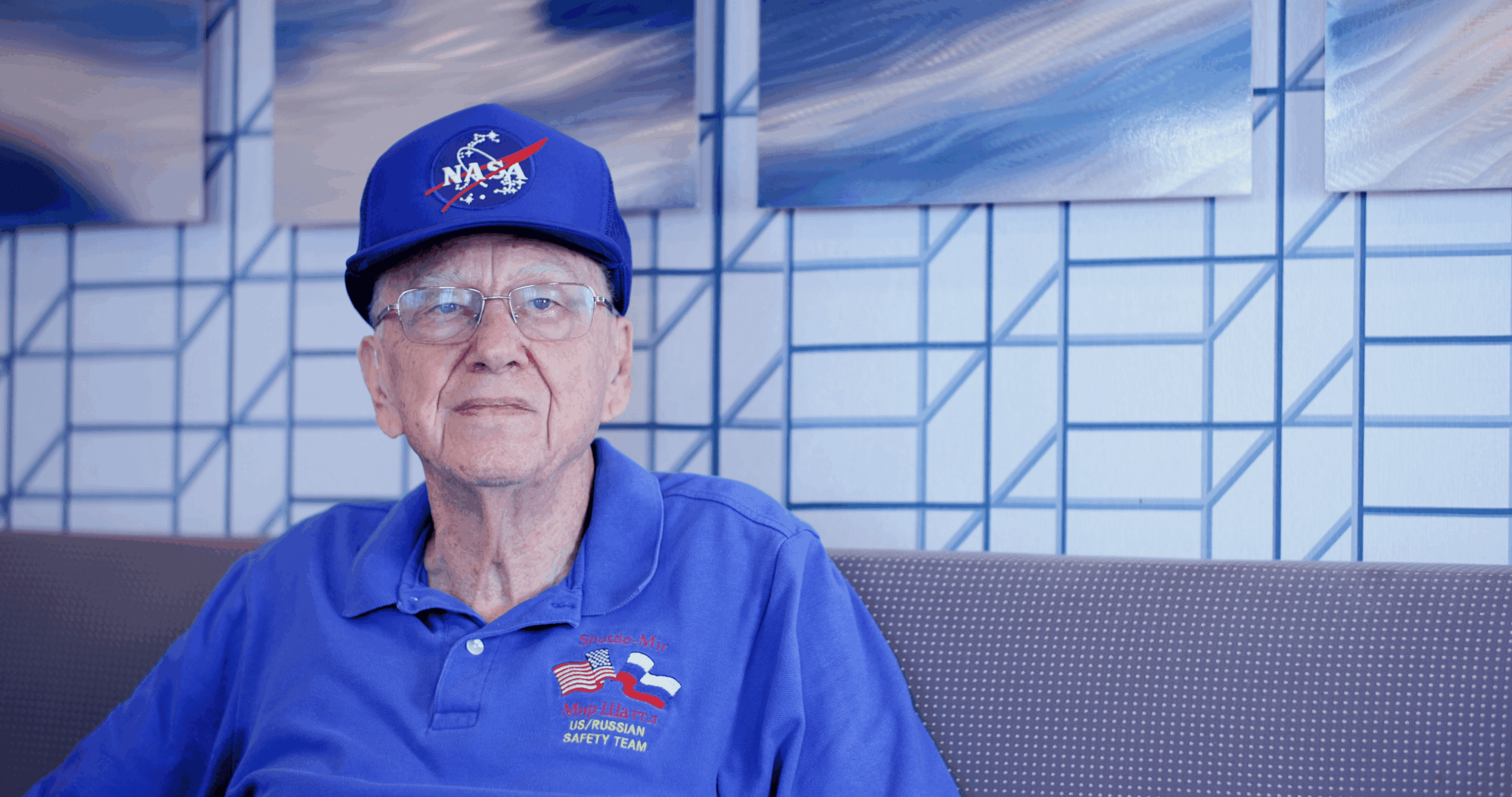

When he arrived at NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center, the race to the Moon was in full sprint. Johnson joined the Power Distribution and Sequencing Section, a role that would make him responsible for one of the most critical systems on Apollo: the sequential events control system—the mechanism that fired separation pyros, powered abort systems, and guided the spacecraft safely home.

“It was the system that saved lives,” Johnson said. “It controlled the pyrotechnics that separated stages, deployed parachutes, and pressurized fuel lines. If something went wrong, it had to work perfectly—every time.”

When Systems Were Tested by Fire

Johnson’s first real test came at White Sands, New Mexico, during an abort system trial. “The rocket lifted off and one of the fins failed hard-over—it started spinning. The wires broke, triggering an automatic abort. Even spinning at a high rate, the system separated, deployed the parachutes, and landed safely,” he said. “That’s when I knew how much was riding on our work.”

His section’s work extended across both the Command and Lunar Modules, ensuring every sequence—separation, deployment, reentry—fired precisely in order. “There were no second chances,” he said. “We lived by testing. Everything was tested for vibration, shock, thermal vacuum, fault tolerance. Qualification meant survival.”

The Apollo Engineer’s Mindset

Johnson’s generation worked under intense pressure, with an unwavering focus. “We had one goal—to reach the Moon before the end of the decade,” he said. “The Russians were ahead of us. That motivated everyone. We wanted to be the team that beat them.”

His recollections reveal the Apollo engineer’s ethic: rigorous, practical, and driven by accountability. “When Challenger happened years later, the hardest lesson was realizing how easy it is to overlook small problems when you’re getting by. You have to listen to your engineers. You can’t let schedule or politics override safety.”

The Tom Hanks Moment

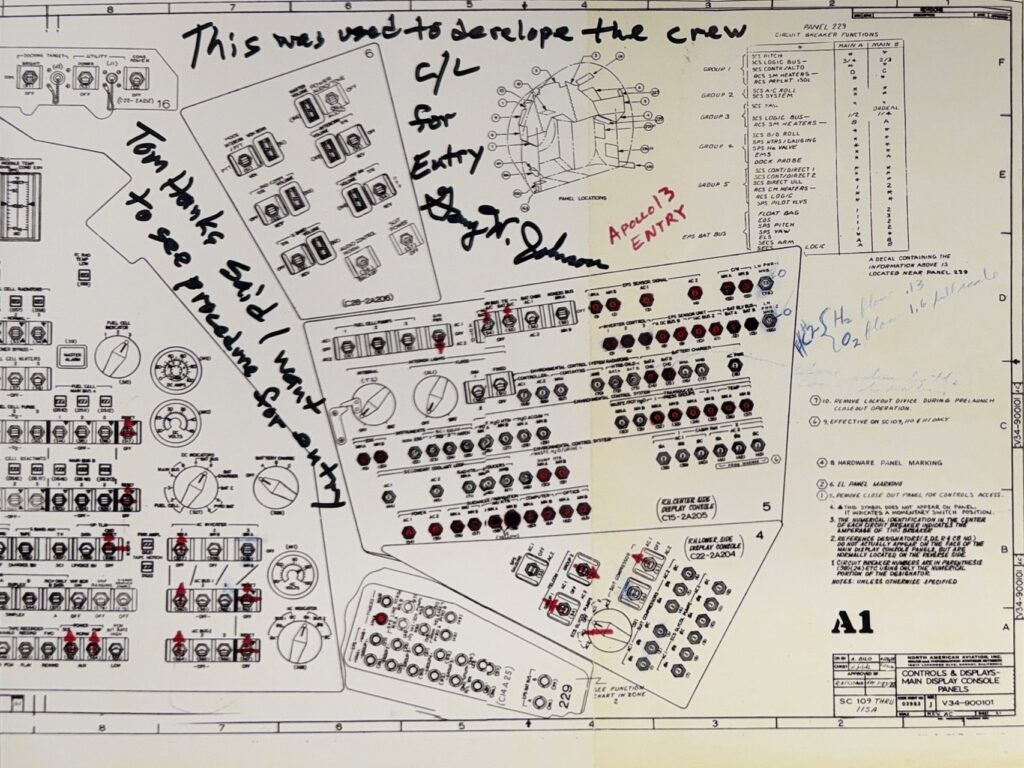

When I interviewed Gary for Before the Moon, he showed me this incredible artifact (which he signed for me) — a control panel schematic used to develop the Apollo 13 entry checklist. The sheet, marked “Controls & Displays – Main Display Console Panels,” is covered in tiny red annotations and handwritten notes. Across the top, Gary had written: “This was used to develop the crew checklist for Entry – Gary Johnson – Apollo 13 Entry.”

He told me, laughing, that years later when Tom Hanks visited NASA while preparing for the film Apollo 13, Hanks wanted to see “the real thing” — not a prop, but the actual procedures the engineers had used. “Tom Hanks said, ‘I want to see the procedure for entry,’” Gary recalled. “So I pulled this out — the very one we used to build the checklist that got them home.”

It’s a powerful reminder that behind every iconic moment of the space program — like the Apollo 13 re-entry — were engineers like Gary, sitting over blueprints like this one, figuring out which switch to flip and when, to bring astronauts safely back to Earth.

Designing for the Unknown

From Apollo to Skylab, Shuttle, and ISS, Johnson helped evolve spacecraft power and safety systems across eras of human spaceflight. He transitioned from analog circuits to digital control systems, helped design the Shuttle’s electrical power distribution, and later served as Deputy Director of Safety, Reliability, and Quality Assurance.

“The Shuttle’s power system was far more complex,” he explained. “We went from mechanical relays to computer-driven data buses. But the fundamentals—redundancy, safety margins, fault tolerance—never changed.”

The Centrifuge, Human Limits, and Design Margins

Johnson’s work as an engineer often depended on lessons learned from facilities like the Johnsville Centrifuge in Warminster, Pennsylvania—the same centrifuge that trained the original Mercury astronauts. “Those early tests were vital,” he said. “They showed what the human body could endure. It taught us how much margin we needed to build into our systems.”

One story still stands out: “Frank Borman used the centrifuge to prove he could manually fly reentry without a computer,” Johnson said. “He sat in the centrifuge at four Gs, operating switches to make sure it could be done. That gave us confidence in the manual backup procedures we later relied on.”

Lessons from Apollo 13 and the Unsung Contractors

When Apollo 13’s service module exploded, Johnson watched from the engineering consoles. “The procedures went out the window,” he said. “Everything depended on engineers and contractors improvising in real time.”

He credits those teams for saving the crew. “Without the contractors, Apollo 13 would have failed. The engineers at Grumman, Rockwell, and the Johnson Space Center all worked nonstop to find solutions,” he said. “They built new procedures from scratch to stretch the lunar module’s batteries and life support.”

When I told him that the square-to-round CO₂ canisters used to save the crew were actually designed and built by Lavelle Aircraft Corporation in Newtown, Pennsylvania, he paused. “I didn’t know that,” he admitted. “But it doesn’t surprise me. That’s exactly how NASA worked—contractors and engineers together. It took all of us.”

The Human Side of the Space RaceDespite decades of technical work, Johnson is most proud of the people behind the programs. “My boss told me early on—take your family when you travel, even if it’s a cheap motel. It keeps you grounded,” he said. “A steady family makes everything else possible. We lost too many marriages in those years because the job took everything.”

He never forgot what drove him, or his generation. “I was glad to be part of the generation that beat the Russians to the Moon,” he said simply. “That was history—and I was lucky enough to help make it.”

Gary Johnson signed NASA Engineers Support Apollo 11. Gary in striped dark shirt.

Support the Film

Help us tell the stories of space pioneers like Gary Johnson.

• Visit BeforeTheMoonFilm.com

• Support the film through our donation page

• Follow us on Facebook: facebook.com/BeforeTheMoonFilm

Because before we go forward… we need to remember who got us here.

Leave a Reply