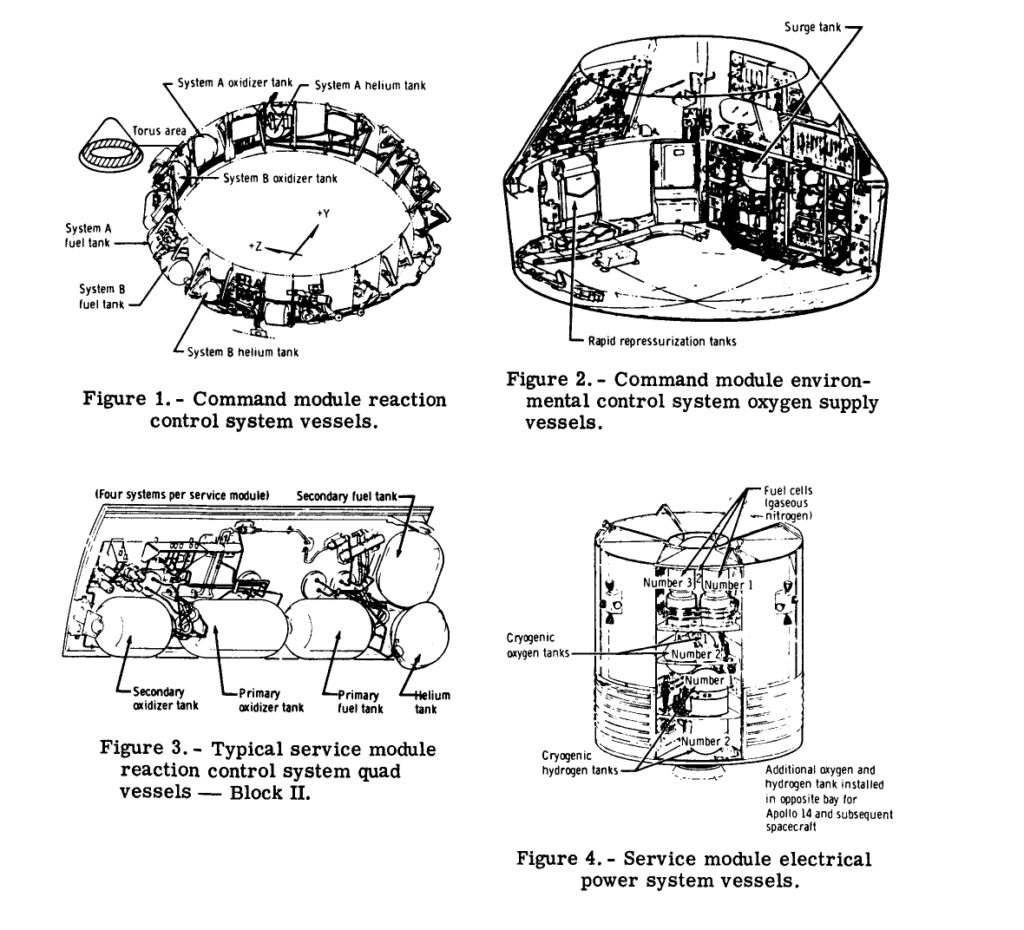

When Glenn Ecord joined NASA, he stepped into a program racing toward the Moon and fighting the limits of physics itself. “I came to NASA in 1966,” he said. “My first assignment was fixing pressure vessels that were failing. When one fails, it doesn’t just leak—it explodes.”

Ecord spent 41 years in NASA’s Materials and Structures Division, investigating the unseen components that kept astronauts alive: the pressure vessels, tanks, and metal shells that had to survive forces no one had ever measured before. His work—documented in his Apollo Experience Report on Pressure Vessels—became a cornerstone of spacecraft safety for decades to come.

Engineering at the Edge of the Unknown

“When I arrived, North American Aviation and Grumman were the designers,” he explained. “We were the troubleshooters. If something went wrong, it came to us.”

That “something” happened often. During Apollo’s early years, engineers discovered that some titanium pressure vessels had dangerously low safety factors. “We found vessels that could fail catastrophically under load,” he said. “It was very strange—one manufacturer was fine, the other wasn’t. We had to find out why before anyone went to the Moon.”

Their investigations led to new testing methods, materials standards, and safety factors that remain in use today. “Everything we fixed on Apollo carried forward,” Ecord said. “There were no more problems after that.”

Learning from Explosions

When Apollo 13’s oxygen tank ruptured in 1970, Ecord immediately recognized the danger. “It was a unique pressure vessel,” he said. “A short inside caused a fire, and the tank exploded. It was handling damage, not design, but we learned from it.”

Ecord helped develop inspection and stress-corrosion testing techniques to prevent future failures. “When these vessels go, it’s an explosion. You don’t get second chances,” he said. “After Apollo 13, changes were made—and they’ve lasted.”

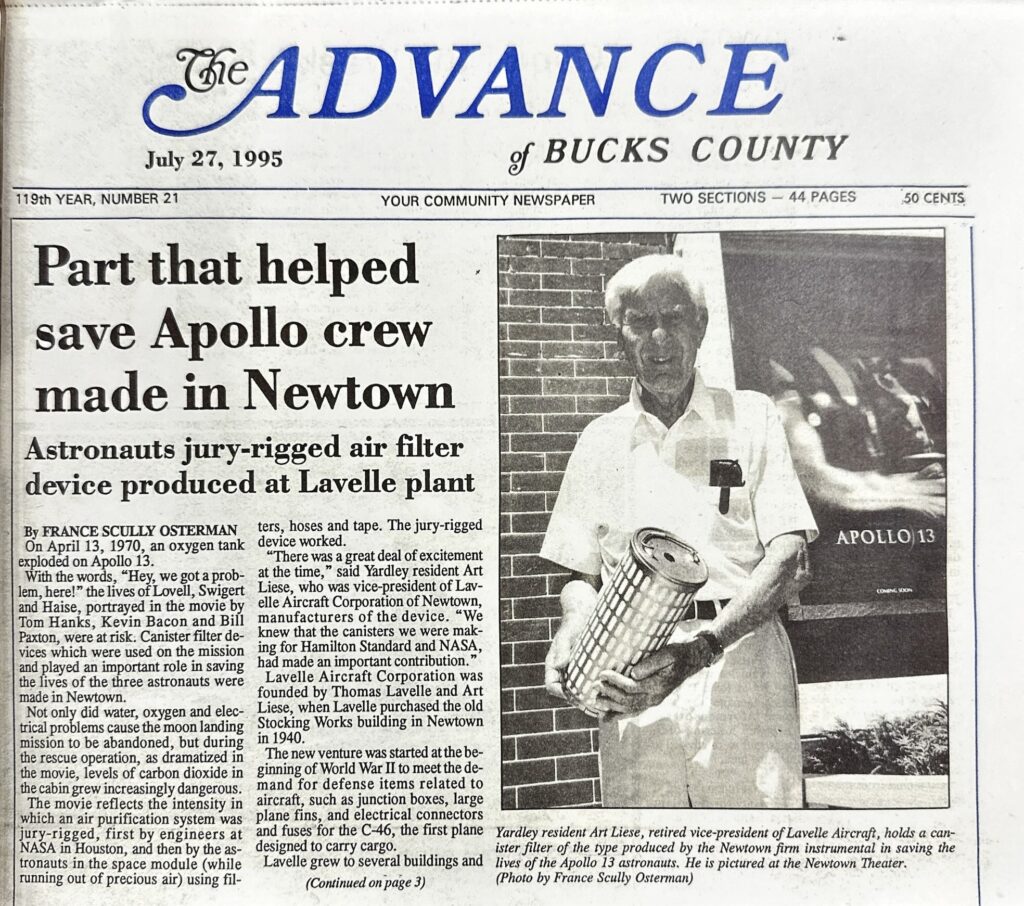

The Canisters That Saved Apollo 13

While much of Apollo 13’s story focuses on Mission Control and the crew, Ecord emphasized the importance of NASA’s contractors. “As I understand it, the cartridges were there to take carbon monoxide out of the air. There would have been no survival without them,” he said. “If it wasn’t for those cartridges, the astronauts would not have survived.”

Those cartridges were built by Lavelle Aircraft Corporation in Newtown, Pennsylvania—the same company whose ingenuity helped engineers on the ground create the “square peg in a round hole” solution dramatized in Apollo 13. “You can’t do anything without the technology that comes from contractors,” Ecord said. “They were essential.”

The Centrifuge and the Human Limits

Though Ecord’s expertise was in materials, he understood the vital role of human endurance testing at facilities like the Johnsville Centrifuge in Warminster, Pennsylvania. “The centrifuge testing was an important factor,” he said. “We needed to know if humans could survive the loads of launch and reentry. That’s where NASA started.”

Those tests directly influenced spacecraft design margins, proving that both hardware and humans could survive the extreme conditions of spaceflight.

Working with Contractors and Building Trust

Ecord’s division depended on data from across the country. “The research and development done by contractors was essential,” he said. “We couldn’t have succeeded without them. The data they provided on materials and failure modes was invaluable.”

NASA’s model of open collaboration between civil servants and private industry became a foundation for its success. “That’s how it worked,” he said. “They built, we tested, and together we learned.”

Lessons That Lasted Beyond Apollo

Ecord’s later work extended through the Shuttle and Space Station programs, where lessons from Apollo’s failures became safeguards for future crews. “Apollo taught me more than anything else,” he said. “It showed me how to avoid problems and how to solve them. What I learned then served me for the rest of my career.”

If he could change one thing, he said, it would be to never compromise on safety margins. “I’d keep a safety factor of two or greater,” he said. “And always test for compatibility—because that’s where trouble hides.”

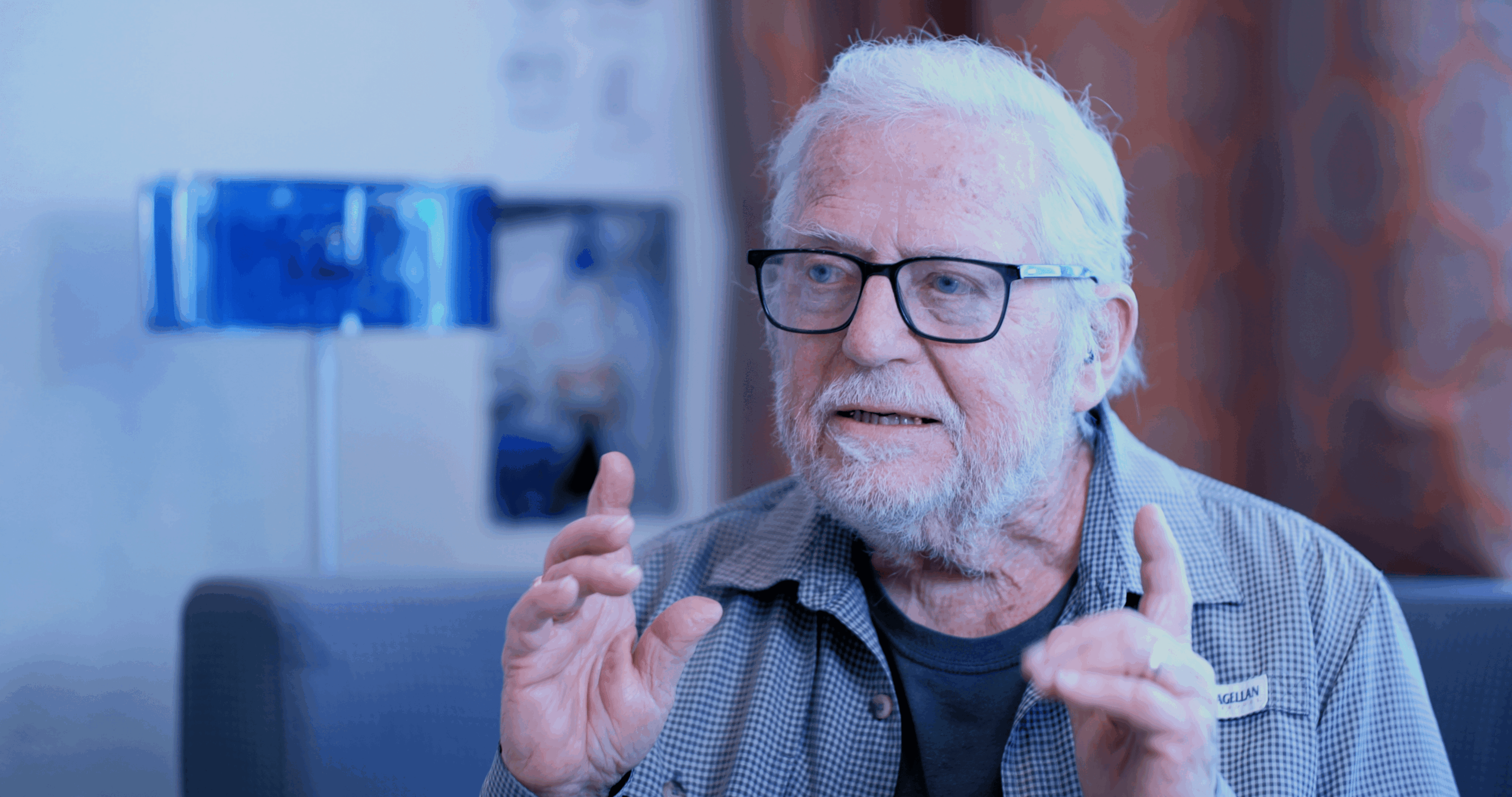

Preserving the Story of NASA’s Success

When asked why it’s important to preserve stories like his, Ecord answered without hesitation. “NASA is an example of success,” he said. “It’s research and development put to real use. People need to know the challenges, the risks, the unknowns. You can’t eliminate them all, but you can face them—and fix them.”

His career, like so many others from the Apollo generation, stands as proof that history’s greatest achievements are built not just on vision, but on quiet, painstaking engineering.

Support the Film

Help us tell the stories of space pioneers like Glenn Ecord.

• Visit BeforeTheMoonFilm.com

• Support the film through our donation page

• Follow us on Facebook: facebook.com/BeforeTheMoonFilm

Because before we go forward… we need to remember who got us here.

Leave a Reply