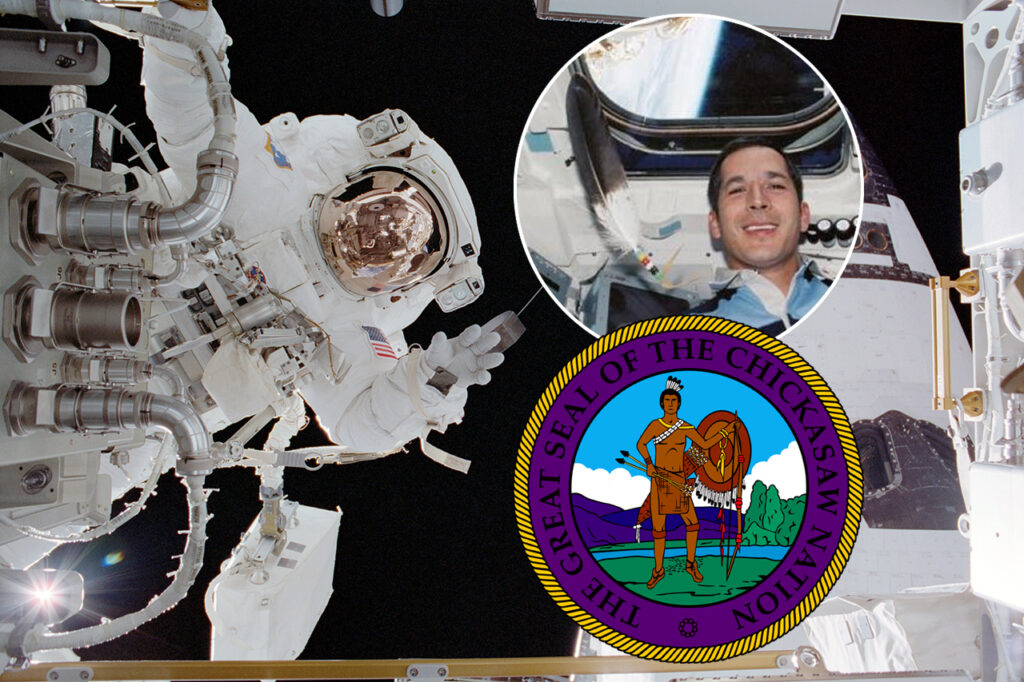

When John Herrington floated out of the Space Shuttle Endeavour in November 2002, he carried more than tools and tether lines. He carried a story—a legacy. As the first Native American in space, Herrington’s mission wasn’t just about walking in the void. It was about representing an entire community that had never seen itself reflected among the stars.

“Estella Gillette was on my astronaut interview panel,” he said. “She told me, ‘John, you’re the first citizen of a federally recognized tribe to be part of the astronaut corps.’ That’s when I realized the responsibility that came with it.”

The Making of a Spacewalker

Herrington’s journey began in small airplanes, long before NASA flight suits and mission patches. “My dad was a certified flight instructor,” he recalled. “We had an Aeronca Champ and later a Cessna 150. I learned to fly sitting on his right side while he leaned over me to take pictures out the window.”

That early love of flight turned into a naval aviation career, test pilot school, and eventually, astronaut training. But becoming an astronaut wasn’t easy. “I applied first as a pilot,” he said. “NASA wanted a thousand hours of tactical jet time—I didn’t have it. So the second time I applied, I went for mission specialist. They’re the ones who get to walk in space. The pilots usually don’t.”

Learning to Think Ahead of the Switches

As an astronaut candidate, Herrington found his test pilot training indispensable. “Every system you learned had to be understood completely,” he said. “It wasn’t just knowing which switch to throw—it was knowing why. What happens when you throw it, what’s next, and what might go wrong two steps later.”

That mindset carried into his work aboard the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station. “Simulators were brutal,” he laughed. “They’d fail two engines on you during launch just to see how you’d react. Your hair’s on fire, and you’ve still got to make the right call.”

From Centrifuges to Spacewalks

Like generations of astronauts before him, Herrington trained in centrifuges to prepare for the physical strain of launch and reentry. “You’d fly a shuttle profile—two Gs on ascent, up to three by the final minute,” he said. “Mercury and Gemini astronauts pulled more. But that centrifuge training connected us to them—it was part of the culture.”

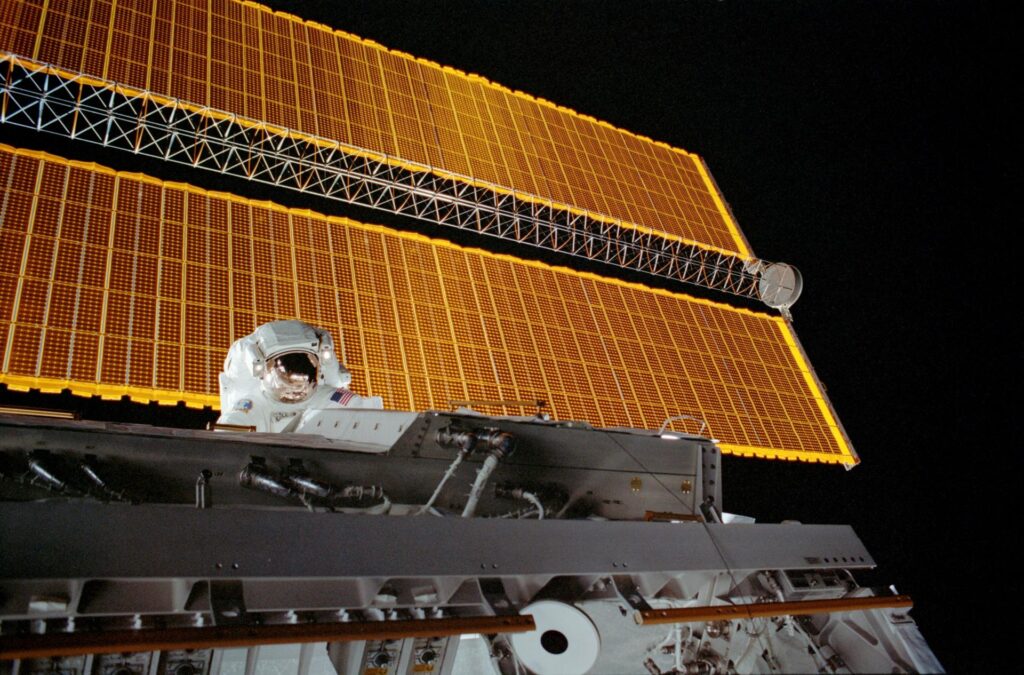

He also credited the Neutral Buoyancy Lab (NBL) with giving astronauts muscle memory for extravehicular activity (EVA). “The NBL was critical,” he said. “You learned the choreography—translation paths, procedures, where your tools are. But space isn’t water. In the pool it’s hard to start and easy to stop. In space it’s easy to start—and hard to stop. Slower is faster.”

When Things Go Wrong

During one EVA, Herrington realized he had inventoried the wrong tool. “I was hanging off the truss, ready to install an antenna, and the extension I brought didn’t fit,” he said. “I felt sick. You don’t fear dying—you fear making a mistake.”

Instead of panicking, he improvised. “I radioed Houston and said, ‘What if I remove this part and work around it?’ They talked to the engineers who’d trained me—Dana Weigel, Karina Shook, Barb Morgan—and came back with ‘Go for it.’ That training paid off. You can’t just follow procedures; you’ve got to have the common sense to solve problems.”

That same adaptability, he said, came from a lifetime of working with tools, cars, and airplanes. “Being handy on Earth saves you in space.”

The People Who Make Flight Possible

Herrington never misses a chance to credit the people on the ground. “If they didn’t do their job, we couldn’t do ours,” he said. “From the trainers and suit techs to the engineers and closeout crews at the Cape—those folks treat the Shuttle like it’s their baby. Their pride and craftsmanship make human spaceflight possible.”

He often remembered the words of his mentor, astronaut Jerry Ross:

“Never forget—you’re standing 195 feet up on the shoulders of the people who made it possible.”

Herrington nodded as he repeated it. “That’s the truth. It’s not about profit or a product. It’s about a purpose.”

Culture, Legacy, and the Next Generation

As the first Native American astronaut, Herrington felt the weight—and opportunity—of representation. “I found myself a role model for kids who never had one,” he said. “That’s why, later in life, I earned a Ph.D. in education, studying what motivates Native students to learn science and math. It comes down to hands-on learning—working with friends, building things, understanding why something works.”

When he speaks to students, his message is simple: “Math isn’t abstract. It’s real. You see it on every instrument panel, every calculation that keeps you alive. If you can do the math, you can do anything.”

Learning from Mistakes—and the Planet Itself

For Herrington, preserving NASA’s history is more than honoring the past—it’s about avoiding its missteps. “Learn from your mistakes,” he said. “When you read the Columbia and Challenger accident reports, you see the same patterns. We can’t let those happen again.”

He believes the future of exploration must also reflect humanity’s lessons on Earth. “People talk about terraforming Mars,” he said. “But we already have an Earth—and we’re not taking care of it. If the launch pad is underwater, we’re not going anywhere. Whatever we do out there has to benefit life down here.”

The Spirit of Exploration

As NASA prepares to return to the Moon with Artemis, Herrington sees hope in its diversity. “Look at Artemis—men, women, people of color. That’s what space should look like,” he said. “Diversity isn’t a weakness. It’s what makes us strong. Everyone brings something different to the table.”

His final thought captured the heart of Before The Moon:

“We do this not for a company, not for a country, but for a purpose—to make life better for everyone. That’s what exploration is about.”

Support the Film

Help us tell the stories of space pioneers like John Herrington.

• Visit BeforeTheMoonFilm.com

• Support the film through our donation page

• Follow us on Facebook: facebook.com/BeforeTheMoonFilm

Because before we go forward… we need to remember who got us here.

Leave a Reply