In the quiet heart of Warminster, Pennsylvania, beneath the shadow of shopping centers and suburban streets, lies a history that once helped power the Space Race. Eleanor O’Rangers, President of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Cold War Historical Society, has dedicated her career to uncovering it. “Most people think of Bucks County as the birthplace of America,” she said. “But it was also the birthplace of the technologies that carried us to the Moon.”

For O’Rangers, preserving that story isn’t nostalgia—it’s an act of national memory. “It’s not just about the Revolutionary War anymore,” she explained. “It’s about the revolution of the future.”

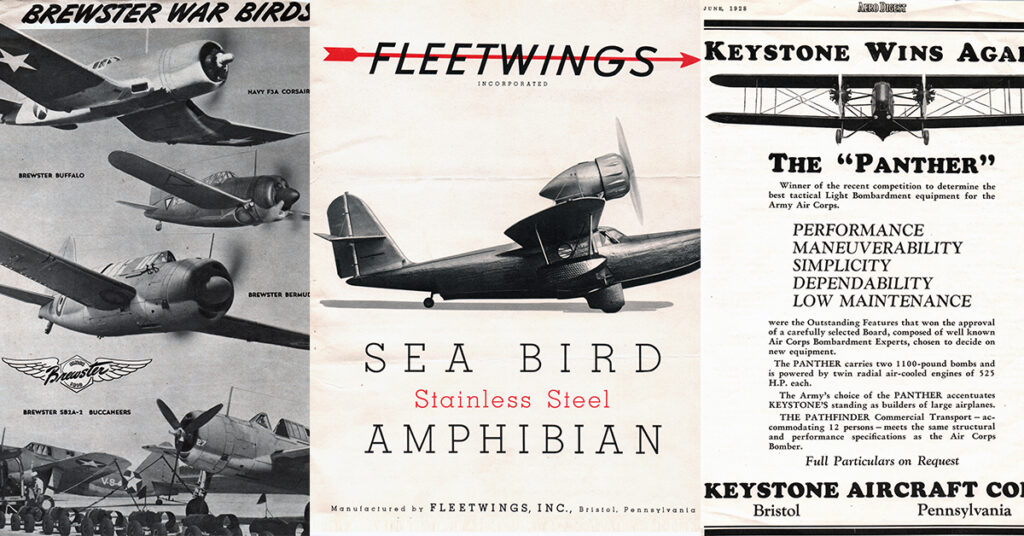

From Carriages to Corsairs: The Rise and Fall of Brewster Aeronautical

The story begins with the Brewster Aeronautical Corporation, a company that transformed from a carriage maker in New York into an aircraft manufacturer in Warminster during World War II. “They had contracts, big dreams, and a reputation for trouble,” O’Rangers said. “But they never managed to get a single viable aircraft off their assembly line. Eventually, the government stepped in and seized the operation.”

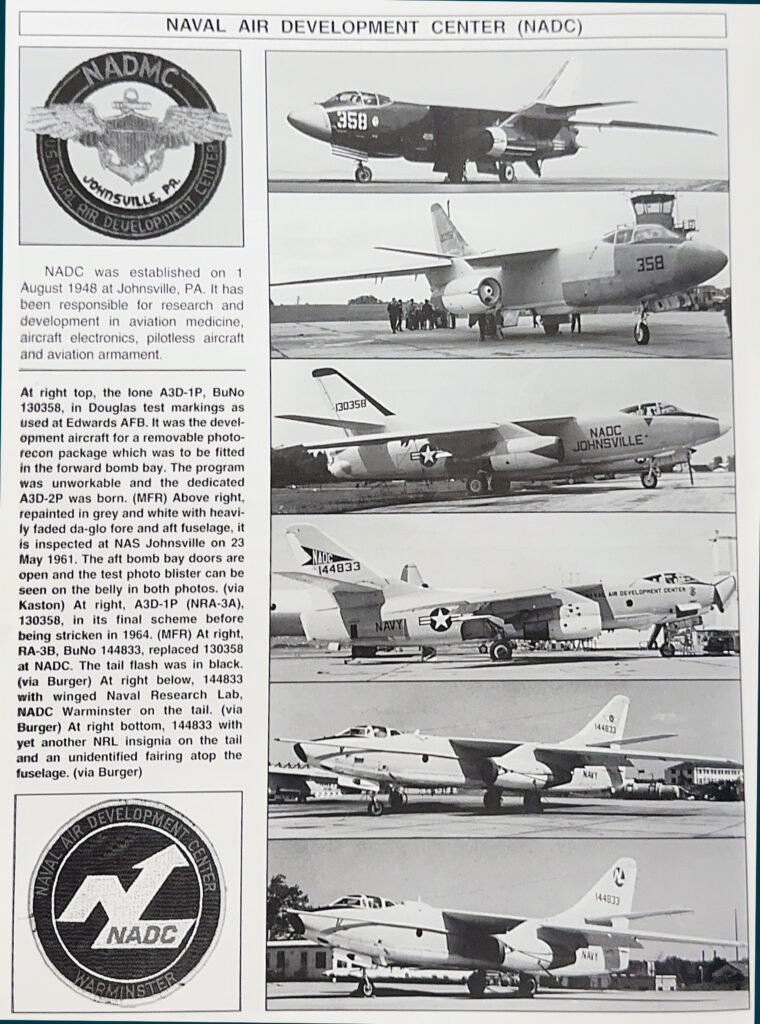

When Brewster finally collapsed, the Navy inherited its 800-acre property—and a blank slate. That land would become the beating heart of America’s naval aviation research: the Naval Air Development Center.

Keystone, Fleetwings, and the Birth of Bucks County Aviation

Long before NASA arrived, Bucks County was already innovating in the skies. “Fleetwings in Bristol built amphibious aircraft entirely from stainless steel,” O’Rangers explained. “It was cutting-edge technology for the 1930s—some of their engineers even came from Germany to teach the craft.”

The Navy soon realized the potential of this corridor between Philadelphia and Trenton. “After World War II, they converted the old Brewster site into a research hub,” she said. “What began as the Naval Air Modification Unit evolved into the Naval Air Development Center—where everything from missile guidance to astronaut training would take shape.”

Warminster and the Space Race

When NASA needed a place to train its first astronauts for the brutal forces of launch and reentry, there was only one centrifuge powerful enough. “Johnsville’s centrifuge was the largest, most powerful human centrifuge ever built,” O’Rangers said. “It could generate 40 times the force of gravity. That’s why NASA chose it for the Mercury astronauts.”

The centrifuge was more than a machine—it was a simulation laboratory. “They designed programs to help astronauts understand what their bodies would experience in space,” she explained. “It made them ready for anything.”

The Unsung Heroes: Lavelle, RCA, and the Birth of Nomex

O’Rangers’ research also shines a light on the small companies that quietly shaped the space program. “Lavelle Aircraft Corporation in Newtown built stainless steel parts for the Lunar Module,” she said. “They made the lithium hydroxide canisters that saved the Apollo 13 crew. Most people don’t realize that piece of history happened right here in Bucks County.”

Other Pennsylvania innovators left their mark as well. “Philco-Ford in Lansdale built the integrated circuits that powered NASA’s computers,” she said. “RCA in Camden designed the telemetry systems that monitored astronauts’ heart rates on the Moon.”

And one of Warminster’s greatest scientific pioneers, Dr. Alice Stoll, changed safety forever. “She invented Nomex—the flame-resistant material still used in flight suits, firefighter gear, and spacecraft today,” O’Rangers said. “She also discovered the ‘Stoll Curve,’ defining how much acceleration the human body can withstand. Her research literally helped keep astronauts alive.”

The Cold War, the Centrifuge, and Human Survival

The Naval Air Development Center’s work extended far beyond spaceflight. “They built ejection towers, environmental chambers, and even crash simulators,” O’Rangers said. “They studied how cold water affects survival time and how pilots could survive a helicopter crash. Every test helped make aviation safer.”

She pointed to programs like the P-3 Orion and Sonobuoy systems that were developed at NADC to track Soviet submarines. “Warminster played a major role in Cold War defense,” she said. “It wasn’t just about space—it was about survival.”

The End of an Era

By the 1990s, consolidation efforts under the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Act sealed NADC’s fate. “When the base closed in 1996, we lost more than 3,000 jobs—and a lot of institutional memory,” O’Rangers said. “It was one of the best places to work, and people still mourn its loss.”

Today, the centrifuge still stands—transformed into an event venue but protected as a registered historic landmark. “It’s poetic,” she said. “People celebrate milestones there without realizing astronauts once trained in that same room.”

Preserving the Story

O’Rangers sees her work as part of a mission to honor the people who built America’s path to space. “Pennsylvania doesn’t have an Aerospace Hall of Fame,” she said. “It should. The contributions from this region—from Lavelle to RCA—deserve recognition.”

Her goal is to spark a new kind of pride. “When people think of Philadelphia, they think of the Revolution. But this area helped start another kind of revolution—the technological one,” she said. “The story of Warminster isn’t just local history. It’s American history.”

Support the Film

Help us tell the stories of space pioneers like Eleanor O’Rangers.

• Visit BeforeTheMoonFilm.com

• Support the film through our donation page

• Follow us on Facebook: facebook.com/BeforeTheMoonFilm

Because before we go forward… we need to remember who got us here.

Leave a Reply