When Jerry Ross launched aboard the Space Shuttle for the first time, he was not just fulfilling a childhood dream. He was stepping into a role that would make him one of NASA’s most accomplished astronauts. With seven spaceflights, Ross remains the joint record holder for the most missions in human history. His hands built the early backbone of the International Space Station. His voice guided younger astronauts. His engineering instincts helped save satellites worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

And behind every achievement, he says, was one simple truth.

“I followed the space program from the beginning. I went from wanting to be involved to wanting to be at the very tip of the rocket.”

Ross’s journey from a fourth grade dreamer to a veteran of seven missions is a story of preparation, humility, technical mastery, and an unwavering belief in teamwork.

The Engineer’s Mindset

Ross credits Purdue University, his mechanical engineering background, and a lifetime of problem solving with giving him the mental toolkit that defined his NASA career.

“An engineer by definition is someone who tries to find answers,” he said. “Those tools helped me resolve the issues I faced.”

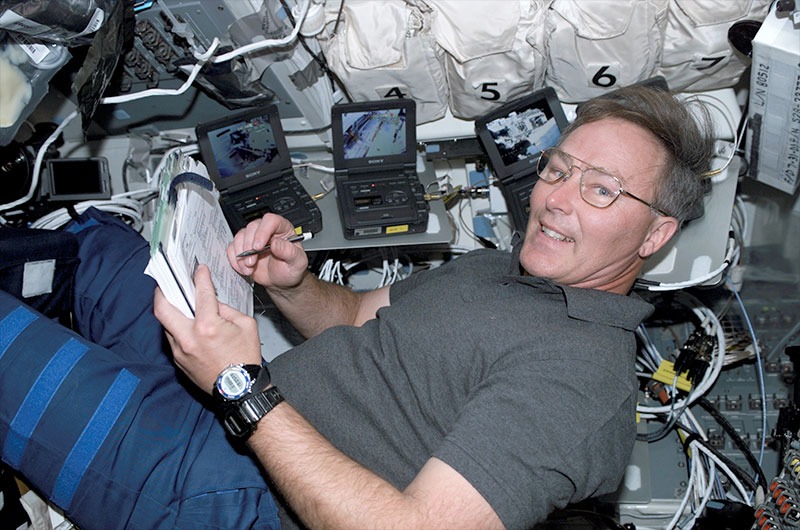

Inside the Shuttle cockpit, that mindset was essential. The Shuttle had more than a thousand switches and circuit breakers, each with unique properties and failure modes. Mastery took years.

“It took a couple of years before you felt halfway comfortable with the systems,” he said. “You had to know how they worked and how they affected everything else.”

Preparing for the Impossible

NASA’s training pipeline is legendary, but Ross describes it not as hardship, but as breadth.

“It wasn’t that anything was extremely difficult,” he said. “It was the sheer scope. We had to know a little bit about everything.”

Between simulations, EVA rehearsals, and water tank training, he and his crewmates learned to anticipate issues before they happened.

And when something did happen, trust in the ground team meant everything.

“We knew those people,” he said. “We had worked long hours with them. Knowing they were still with us during the mission was incredibly reassuring.”

Engineering the Space Station Before It Existed

Ross’s proudest engineering achievement happened before the ISS even reached orbit.

“I pushed to make sure that the space station we were getting ready to build was actually buildable,” he said. “We had to teach contractors what EVA really meant. Some of them only knew how to spell it.”

He insisted that EVA crews be allowed to test hardware in representative environments. His caution paid off. Several pieces of equipment failed in vacuum or thermal testing. Without his push, those components would have failed in space.

Saving a Six Hundred Thirty Million Dollar Observatory

His third mission brought one of the greatest validations of NASA’s philosophy of keeping people in the loop.

Ross and his crewmates deployed the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, a sister instrument to Hubble that was stuck during its remote deployment.

A long, thirty foot antenna boom refused to extend. Without it, the satellite was useless.

Ross went outside.

“We had planned for the possibility,” he said. “We worked with the manufacturer ahead of time to add manual backup features. Because of that, we freed it and deployed it by hand.”

Compton would go on to change astrophysics, forcing scientists to rethink theories about gamma ray sources in the universe.

“It was one of those regular days for an engineer,” Ross joked, “that made scientists rethink everything.”

Moments of Awe

Ross has hundreds of hours of EVA time. But one moment stays with him above all others.

He was resting in darkness, attached to the end of the robotic arm, more than forty feet above the Shuttle.

“I turned off my helmet lights,” he said. “I let my eyes adapt. I had this overwhelming feeling of being at unity with the universe. I felt like I was doing exactly what I had been designed to do.”

That moment captured the heart of his career. Engineering and exploration meeting in absolute silence.

The Power of Humor and Humanity

Training could be grueling, with schedules so dense Ross sometimes missed meals. Humor kept the teams sane.

“We had a couple of characters on my first crew,” he said. “They kept us loose. On other crews we did not have that person, so I tried. Maybe I failed miserably, but at least they laughed at my failures.”

Lessons from the Past, Purpose for the Future

Ross is adamant that future generations must understand that NASA is not built on superheroes.

“It takes everybody,” he said. “Janitors, nurses, lawyers, technicians, engineers. People think astronauts do everything, but we cannot do anything without the team.”

That humility is why he believes telling these stories is essential.

“People look at NASA and think it is too hard to attempt. But we are fairly normal people who worked hard and worked as a team. It was never work to me. It was fun. It was a giant puzzle with a lot of people helping to solve it.”

From Mercury to Artemis, Ross sees the same thread.

“We build on what came before,” he said. “I sought out the Apollo people because they knew how to get things done.”

Now, as NASA returns to the Moon, he sees the importance clearly.

“We are going to the polar regions to harvest water ice. Water lets us live there, and it lets us make rocket propellant. That is how we eventually go to Mars.”

A Moment for the Next Generation

Before we wrapped the interview, Jerry Ross was joined by a young visitor named Brandon Surnitsky, a twelve year old student serving as a production and archival assistant on Before The Moon. Brandon is completing this work as a Chesed volunteer project for his Bar Mitzvah training at his synagogue. His father, Craig, who serves as President of the congregation, reflected on the moment and said, “I’ve watched many students choose service projects, but Brandon’s stood out. He has been passionate about space for half his life, and speaking with a seven time astronaut was, in his words, a once in a lifetime dream.”

Brandon asked Jerry the final two questions of the interview, focusing on STEM education and whether his generation might one day see humans living on Mars. Jerry responded with encouragement, candor, and the same spirit of mentorship that has defined his career. For Brandon, it was an unforgettable milestone. For all of us, it was a reminder of why telling this history matters: every preserved story becomes fuel for the next explorer.

A Final Message from Orbit

Before ending the interview, Ross shared the message every astronaut returns with.

“When you see Earth from above, the atmosphere looks like a very thin blue band. That thin band keeps everyone alive. It shows how important it is to be good stewards of our planet.”

Listen to the Podcast episode here:

Or Watch the Video here:

Support the Film

Help us tell the stories of space pioneers like Jerry Ross.

• Visit BeforeTheMoonFilm.com

• Support the film through our donation page

• Follow us on Facebook: facebook.com/BeforeTheMoonFilm

Because before we go forward… we need to remember who got us here.

Leave a Reply