When people think about the space program, they imagine rockets, astronauts, and launchpads in Florida or Texas. What they rarely picture is a chemical engineering laboratory in eastern Pennsylvania, where fundamental questions about materials, gravity, and matter were being asked decades ago.

Yet that is exactly where Mohamed S. El-Aasser built a career that quietly intersected with NASA, the Space Shuttle program, and the future of materials science.

From his base at Lehigh University, El-Aasser helped answer a deceptively simple question that Earth itself makes difficult to study: how do polymers really form when gravity gets out of the way?

From Alexandria to Bethlehem

Mohamed El-Aasser’s journey into science began far from Pennsylvania. Born in Egypt in 1943, he earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees at the University of Alexandria before continuing his education abroad. In 1972, he completed his Ph.D. at McGill University in Montreal, specializing in chemical engineering and polymer science.

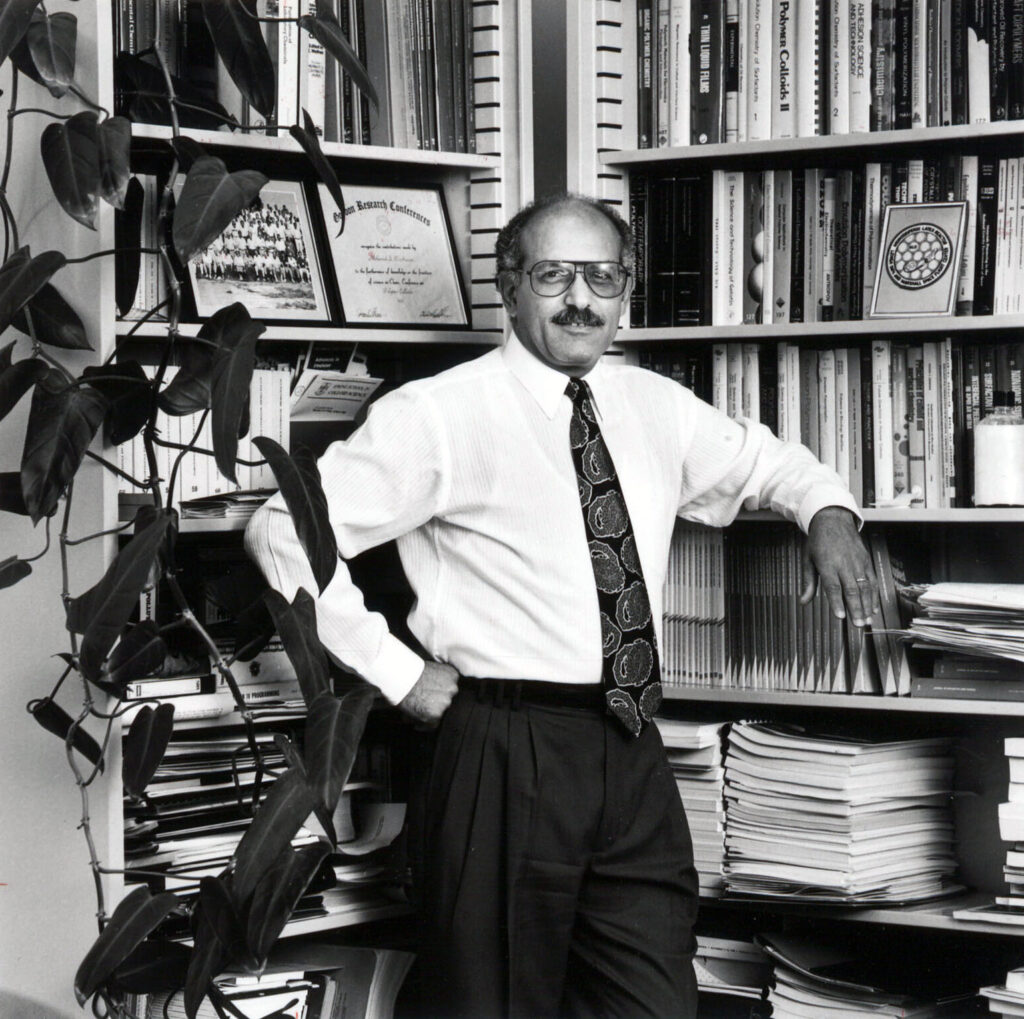

That same year, he arrived at Lehigh University as a postdoctoral researcher. What followed was a career spanning more than four decades at Lehigh, where he rose from assistant professor to full professor and ultimately Professor Emeritus of Chemical Engineering.

Along the way, El-Aasser became deeply embedded in the academic and scientific life of the university. He served as chair of the Department of Chemical Engineering, dean of the P.C. Rossin College of Engineering and Applied Science, provost and vice president for academic affairs, and later vice president for international affairs. His influence extended well beyond his own laboratory, shaping Lehigh’s research culture and global engagement.

A World Authority on Polymer Colloids

Scientifically, El-Aasser is best known for his pioneering work on polymer colloids, particularly emulsion and miniemulsion polymerization. These processes control how microscopic polymer particles form, grow, and stabilize in liquid systems. The implications reach far beyond chemistry textbooks, touching industries ranging from coatings and adhesives to biomedical materials and diagnostics.

Over the course of his career, he authored more than 400 scientific papers, edited multiple books, and held nine U.S. patents. He also mentored an extraordinary number of young scientists, serving as advisor or co-advisor to nearly one hundred doctoral students, along with dozens of master’s students and postdoctoral researchers.

Among his most significant contributions was helping to pioneer the field of miniemulsions, a technique that allows precise control over particle size and structure. This work laid the groundwork for applications that require uniform, highly spherical particles, including drug delivery systems and advanced materials.

Why NASA Came Calling

In the early 1980s, NASA faced a problem that Earth itself made difficult to solve. Many polymerization processes are influenced by gravity. Differences in density cause particles to rise, sink, or aggregate, complicating attempts to create perfectly uniform materials.

Microgravity offered a rare opportunity.

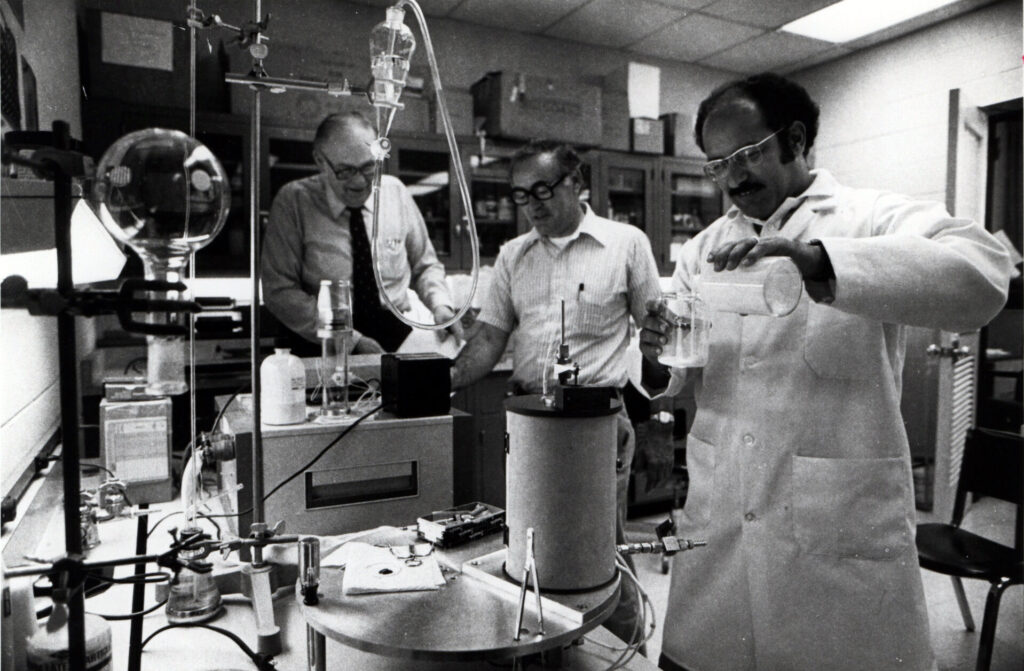

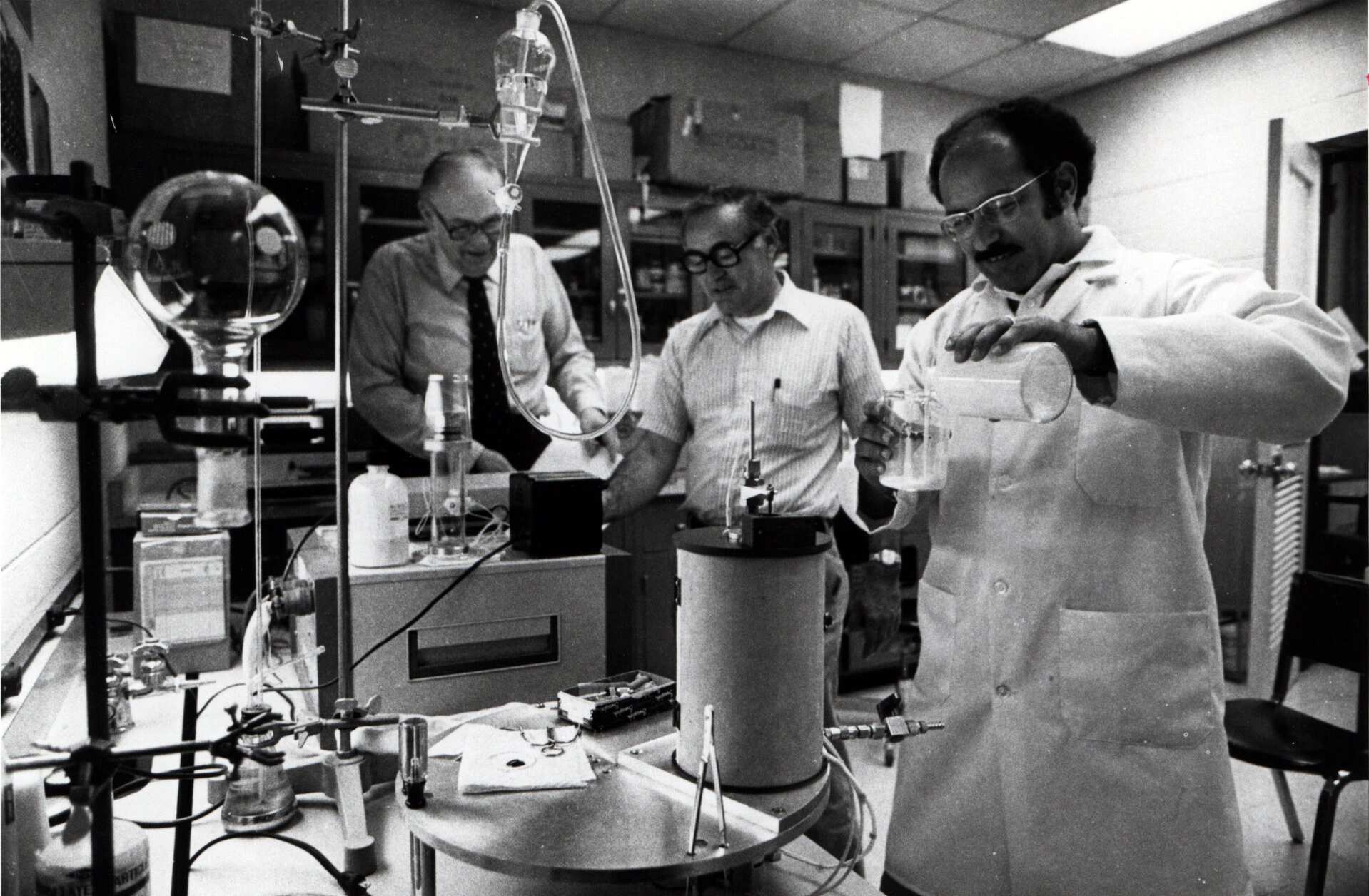

El-Aasser and his collaborators proposed an experiment to study polymerization in space, focusing on the creation of monodisperse latex particles, particles that are nearly identical in size and shape. On Earth, gravity interferes with this process. In orbit, those constraints disappear.

Working with NASA and industry partners, including General Electric, El-Aasser’s team designed compact polymerization reactors capable of operating aboard the Space Shuttle. These were not theoretical exercises. The hardware had to survive launch, operate reliably in orbit, and produce measurable results with minimal astronaut intervention.

Between 1982 and the mid-1980s, four Shuttle-based polymerization experiments were flown. Not all were successful. One failed due to a power issue unrelated to the experiment itself. Others succeeded, producing some of the most spherical polymer particles ever made at the time.

The National Bureau of Standards later described these materials as among the first truly commercial-quality products manufactured in space.

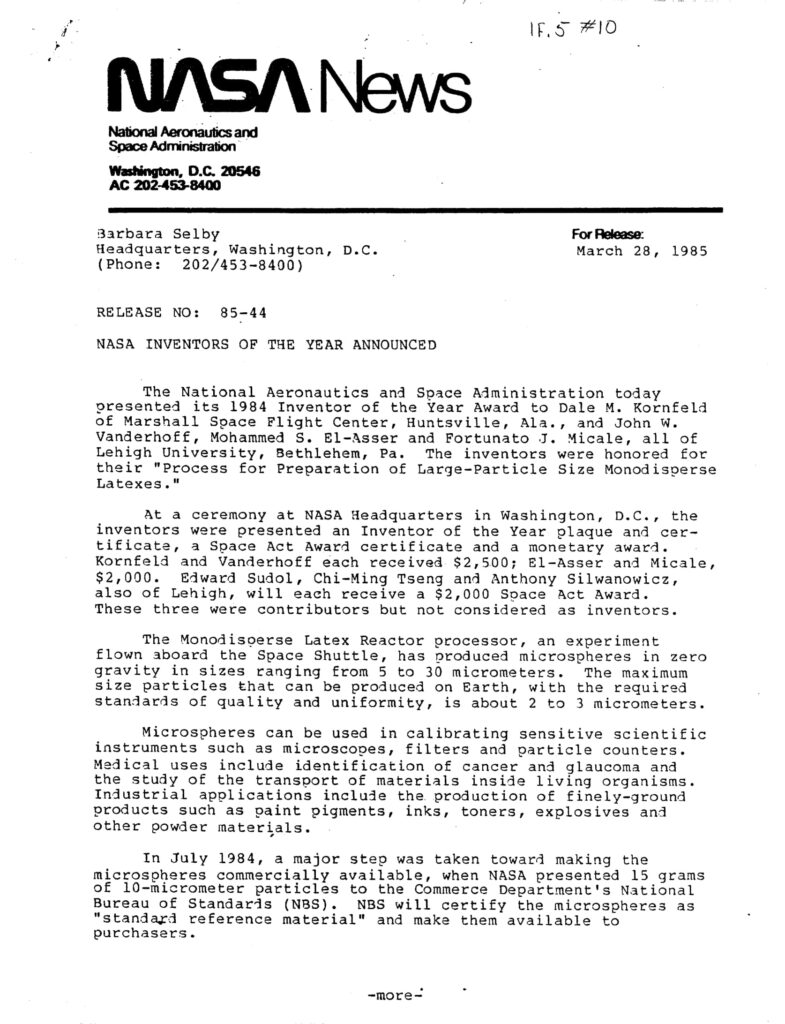

NASA Inventor of the Year

In 1984, El-Aasser shared NASA’s Inventor of the Year Award for this work. The recognition was not just about a single experiment, but about what it demonstrated. Space was not only a destination. It was a laboratory.

From a campus in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, El-Aasser showed that fundamental research conducted far from launchpads could still shape the direction of space science and materials engineering.

Teaching, Mentorship, and Perspective

Despite his accolades, El-Aasser consistently emphasized collaboration and education. He worked closely with astronauts to ensure they understood the chemistry behind the experiments they were running. He encouraged students to study prior research deeply, to publish openly, and to learn from failure as much as success.

His advice to young scientists was pragmatic and enduring: persevere, work with others, and never assume the experiment worked just because you wanted it to.

Why His Story Matters

Mohamed El-Aasser’s career embodies a central theme of Before the Moon. Space history is not only written at launch sites or mission control centers. It is written in university labs, in engineering departments, and by scientists asking careful questions about how matter behaves under extreme conditions.

From Lehigh University to low Earth orbit, El-Aasser’s work reminds us that some of the most important advances in space exploration began not with countdowns, but with equations, experiments, and patient inquiry.

Continuing the Story

Stories like Mohamed El-Aasser’s are part of a broader, often overlooked narrative about how spaceflight has always depended on quiet, distributed innovation.

They are exactly the kinds of stories Before the Moon exists to preserve.

Learn more at https://BeforeTheMoonFilm.com

Follow the project for ongoing research and discoveries

Support efforts to document the scientific foundations of the space age

Because before humanity could explore space, someone had to understand how the smallest particles behaved when gravity disappeared.

Leave a Reply