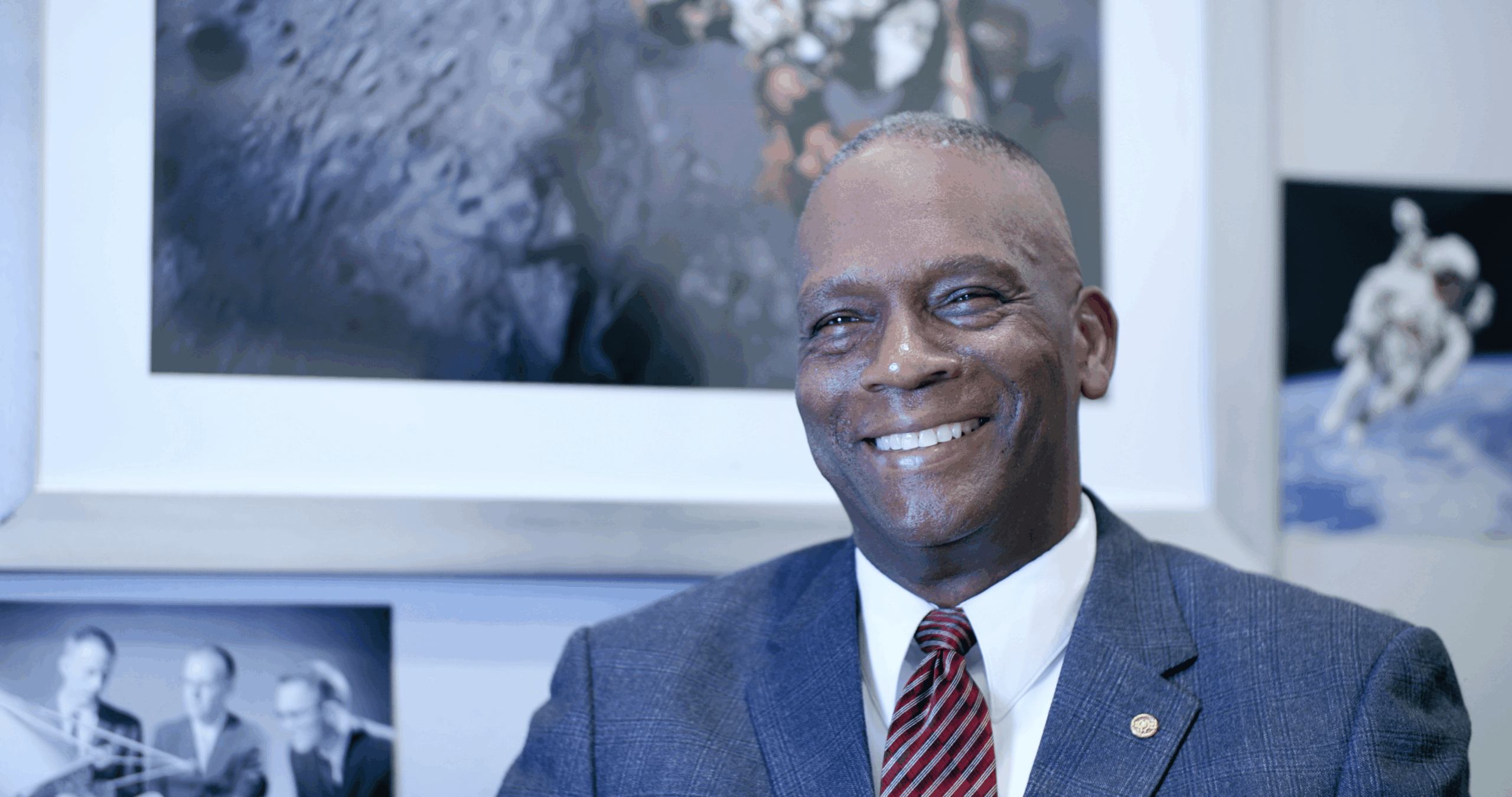

When Ralph Anderson joined NASA, he didn’t know he would one day design a device that could save a drifting astronaut’s life. “I started out as a junior engineer working for Lockheed,” he said. “We built flight crew equipment for the Space Shuttle—a switch panel called L-1011. I couldn’t believe they were going to entrust me to build something that would fly in space.”

That moment launched a career spanning decades, from the earliest days of the Space Shuttle Program to the Safer (Simplified Aid for EVA Rescue) system still protecting astronauts aboard the International Space Station today.

From Lockheed to NASA: Building for the Stars

Anderson’s path to NASA began with encouragement from a college physics instructor. “Her name was Dr. Baines,” he recalled. “She heard me say I wanted to work for NASA and handed me a flyer. I filled it out and sent it in—and sure enough, I got the job.”

His early assignments were humble but critical: building hardware astronauts would use every day. “Very few people get to make something that flies in space,” he said. “It’s exhilarating—and terrifying—because if it fails, lives are at risk.”

That sense of accountability never left him. “In human spaceflight, mistakes can be deadly,” he said. “That’s why documenting lessons learned is so important. As people retire, their voices go silent—and when that happens, old mistakes get repeated.”

Lessons Learned: Writing NASA’s Safety DNA

Anderson was instrumental in building NASA’s “Lessons Learned” database, a cornerstone of its engineering culture. “We created a system where every failure, every fix, and every insight was recorded for future engineers,” he explained. “The next generation shouldn’t have to learn the hard way.”

It was a philosophy born from tragedy. “NASA had to learn from mistakes the hard way—by making them,” he said. “After Apollo 1, Challenger, and Columbia, we realized: our errors stop programs. So we had to make learning part of the culture.”

Designing the SAFER: NASA’s Life-Saving Jetpack

In the mid-1990s, a meeting changed everything. “Bruce Deshaw, the Space Shuttle Program Manager, said they needed a device to save a crew member who drifted away from the Space Station,” Anderson recalled. “He looked around the room and said, ‘Ralph can do that.’ And my boss said, ‘Yes, you can.’ That’s how I got volunteered to build SAFER.”

The Simplified Aid for EVA Rescue (SAFER) became NASA’s first astronaut jetpack—a compact propulsion unit worn on the spacesuit, allowing a stranded astronaut to fly back to safety. “It had to work perfectly the first time,” Anderson said. “Failure wasn’t an option.”

The biggest challenge? A wiring error. “We had a battery wired backward that blew the circuits,” he said. “We caught it just in time for flight.”

Astronauts Mark Lee and Carl Meade were the first to fly the Safer untethered. “They were excited because they knew they were paving the way for future astronauts to save themselves,” Anderson said. “They flew it on a single battery. If it ran out, we’d have to rescue them in real time.”

Thinking Beyond the Obvious

Before Safer, NASA considered ideas that sound wild today: “We talked about lassos, harpoons, even spray cans for propulsion,” Anderson said, laughing. “All of them could’ve gone badly. Safer was elegant—it used small nitrogen thrusters. You could control it with your fingertips.”

That mix of ingenuity and necessity defined Anderson’s entire career. “You find the most creative solutions when you have to build something that doesn’t exist yet—and it has to work,” he said. “That’s how innovation happens.”

Shuttle Engineering: Anticipating the Unknown

As manager of Flight Crew Equipment, Anderson’s team was responsible for the systems astronauts relied on inside the Shuttle. “You never knew what might go wrong,” he said. “We had payload bay doors that wouldn’t open, leaks that threatened the crew, and systems that had to be re-engineered on orbit.”

One of his most creative fixes came during the Shuttle-Mir program. “We had a module that lost oxygen. There was no airlock to get in,” he recalled. “So we came up with a way to perform the first EVA inside a spacecraft. It was risky, but it worked.”

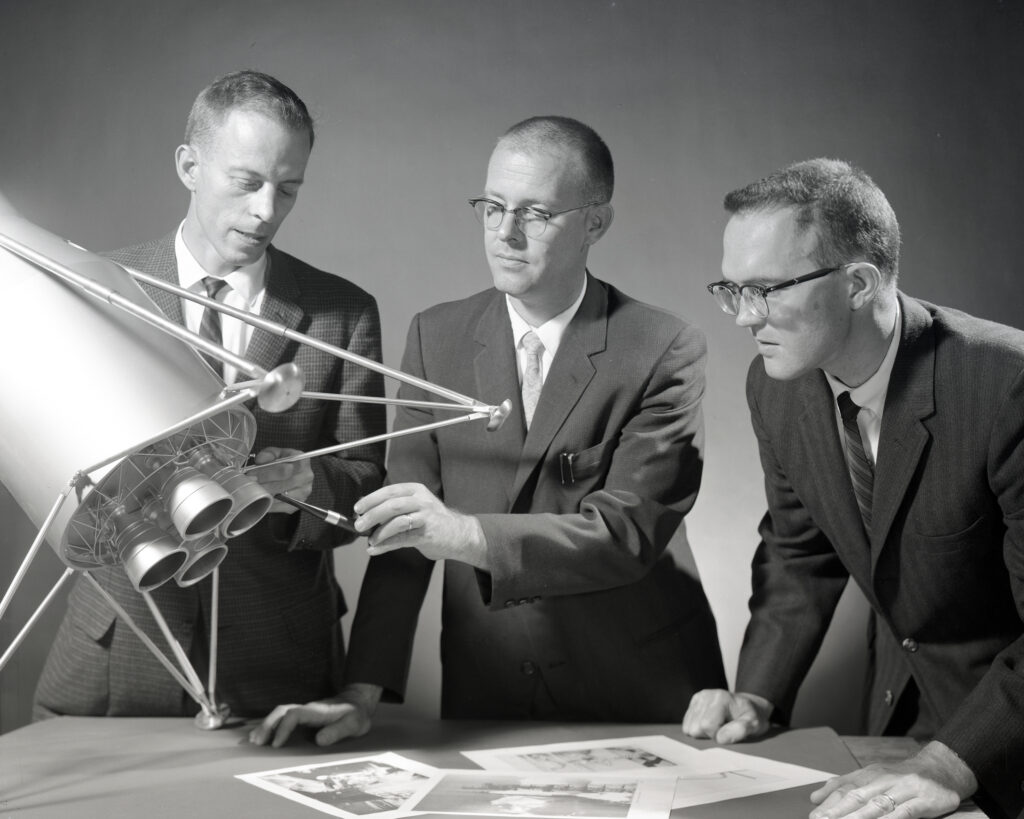

From the Centrifuge to the Shuttle

Anderson sees his work as part of a continuum reaching back to Warminster, Pennsylvania, and the Johnsville Centrifuge where early astronauts trained. “Those people didn’t know how the human body would react in space,” he said. “They figured out what G-forces humans could survive—and we built on that.”

That legacy shaped every program that followed. “From Mercury to Shuttle to ISS, it’s all one story of learning how to keep humans alive in space,” he said. “We stand on their shoulders.”

Breaking Barriers and Building Bridges

As NASA’s first Black manager in the Shuttle Program, Anderson didn’t realize the magnitude of his role until later. “I didn’t know I was changing the culture,” he said. “I just knew I was often the only Black person in the building. That came with pressure—you represent your entire race whether you mean to or not.”

He remembered challenging his colleagues to think about that reality. “I asked them, ‘Would you work in a building where everyone else is Black?’ Dead silence. That’s what it was like for me every day. But you learn to carry that and keep doing the work.”

His success was powered by mentorship. “I had two great mentors—Clay McCulloch and Irv Alexander,” he said. “Without mentors, no one makes it in a field like this. You need someone to give you a chance.”

A Legacy Still Flying

Safer remains in use today—a quarter-century after its creation. “It’s a good feeling to know something you built is still flying,” Anderson said. “That means it worked. Crews still rely on it. Nothing better has come along.”

One of his proudest moments came years later during a Shuttle crew review with Senator John Glenn. “I started the meeting and looked up—there he was,” he said. “I stopped and said, ‘Senator Glenn, I’d like to acknowledge the American hero in the room.’ He smiled and said, ‘Son, go right ahead. You’re doing a fine job.’ That meant everything.”

The Lesson for Future Generations

When asked what he wants young engineers to take from his story, Anderson didn’t hesitate. “Don’t get too proud,” he said. “Someone before you has already solved something just like it. This isn’t a bicycle ride—you can’t pull over if something goes wrong. Focus and stay right.”

He sees storytelling itself as part of the mission. “These stories are our legacy,” he said. “Written words fade, but voices—voices stay alive. This is how we speak to the future.”

Support the Film

Help us tell the stories of space pioneers like Ralph Anderson.

• Visit BeforeTheMoonFilm.com

• Support the film through our donation page

• Follow us on Facebook: facebook.com/BeforeTheMoonFilm

Because before we go forward… we need to remember who got us here.

Leave a Reply