In the early 1950s, inside a restricted Cold War research facility in Warminster, Pennsylvania, a young biophysicist began work that would quietly reshape aviation safety and aerospace medicine.

Her name was Alice Stoll.

She did not arrive as a test subject, a novelty, or a symbol. She arrived as a scientist, recruited for her expertise in heat transfer and human injury at a moment when aviation technology was outpacing biological understanding.

A Scientist Recruited for a Dangerous Problem

Alice Stoll was among the first female biophysicists to graduate from Cornell University. During her graduate studies, she focused on heat transfer, specifically how heat moves between materials and human skin.

That expertise brought her to Warminster, where the U.S. Navy was confronting a deadly and unresolved problem. Jet aircraft were faster and more powerful than ever, but cockpit fires were killing pilots at alarming rates. Nylon flight uniforms, standard at the time, melted onto skin during fires, dramatically worsening injuries.

The question facing the Navy was not theoretical. It was urgent.

Could a fabric be developed that would resist heat long enough to give a pilot time to escape a burning aircraft?

From Heat Transfer to Nomex

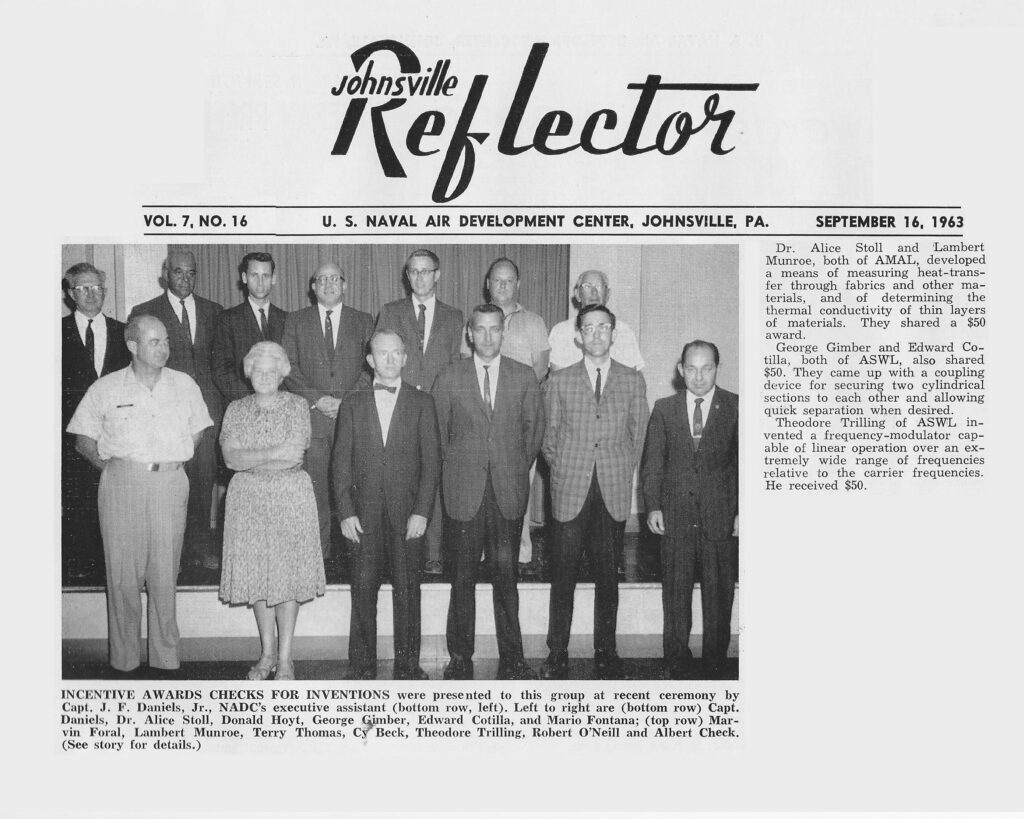

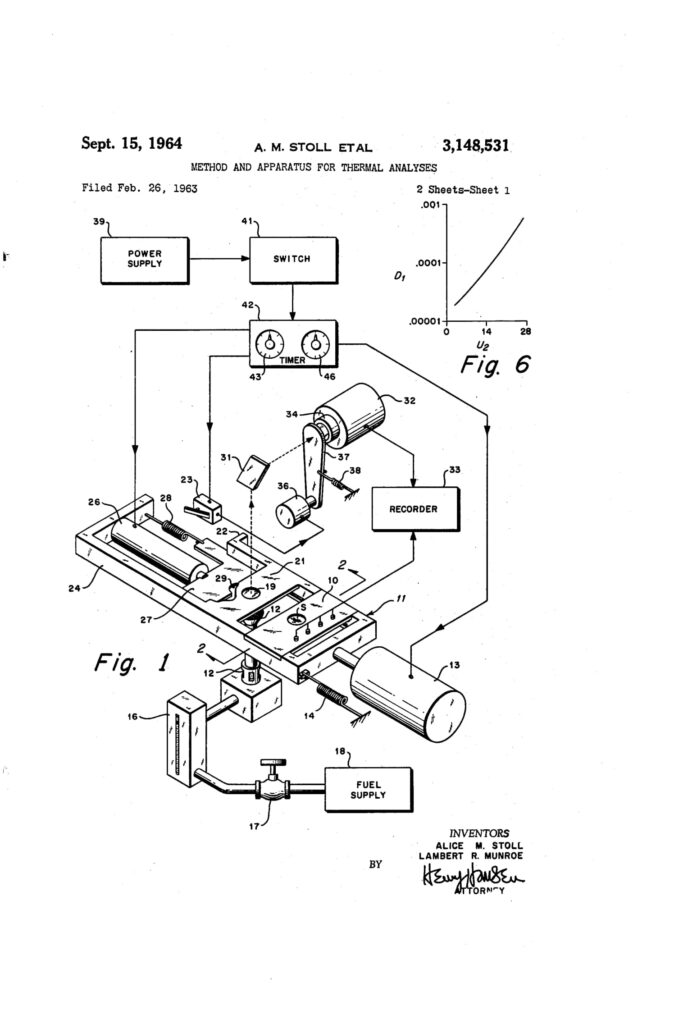

Stoll spent the bulk of her career at the Naval Air Development Center studying thermal injury and heat resistant materials. She systematically evaluated a wide range of high temperature filaments, many developed by DuPont, measuring how heat moved through cloth and into skin.

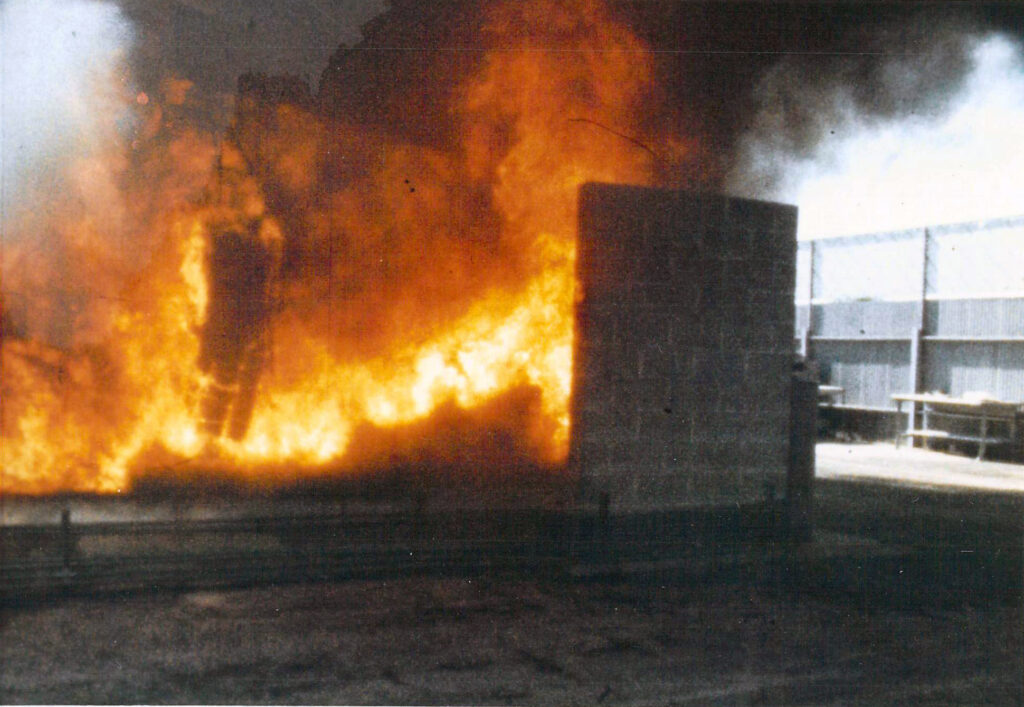

Her work was empirical and rigorous. On base, researchers constructed controlled fire testing environments, including fuel driven flame pits, to expose mannequins wearing prototype flight suits to repeatable fire conditions. The results were measured, compared, and refined.

Through this process, Stoll and her colleagues identified a filament then known as HT-1. Working with DuPont, they helped develop it into a usable cloth. That material would later be named Nomex.

Nomex does not melt. It chars and insulates, buying crucial seconds in a fire.

Today, it is used globally in pilot uniforms, astronaut flight gear, firefighting equipment, industrial safety clothing, and motorsports. Alice Stoll never financially benefited from this work. She regarded it as public service science.

How the Stoll Curve Came to Be

When Alice Stoll first arrived at the base, her heat transfer laboratory was not yet ready. With time available, she walked to another part of the facility where the Johnsville Centrifuge was already operating.

According to Stoll herself, she asked the centrifuge researchers a simple question. Was there any data she could analyze?

They gave her acceleration data that had already been collected, analyzed, and published.

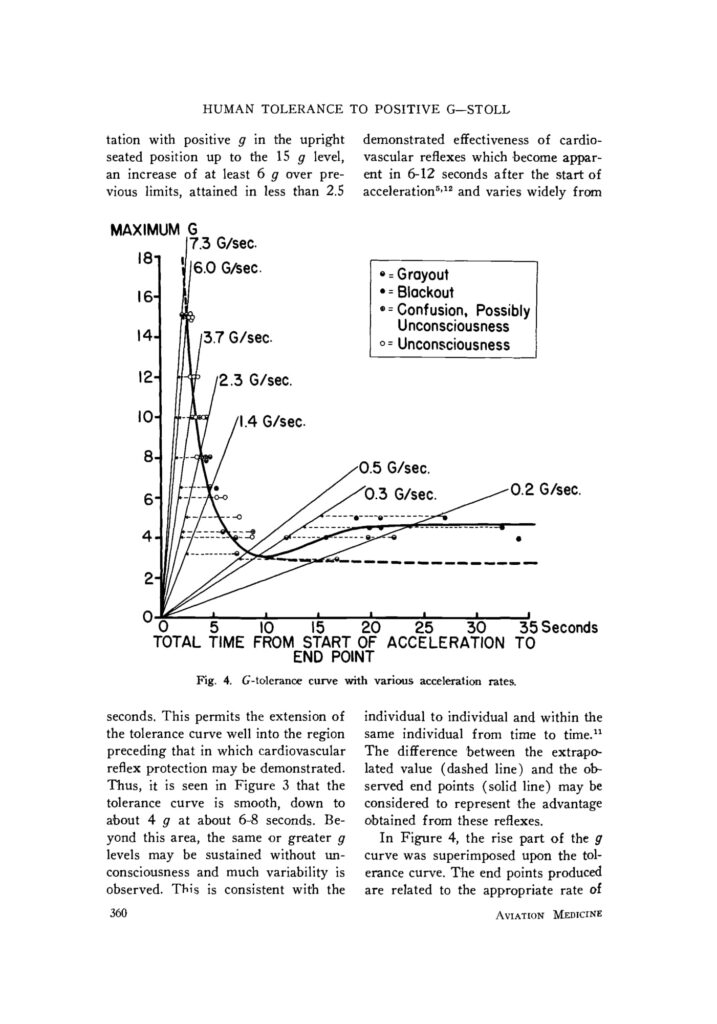

Stoll reanalyzed the data independently.

By examining the information through a different lens, she identified clear thresholds describing human tolerance to acceleration without significant protective measures. Her work defined the relationship between G exposure, duration, and loss of consciousness in a way that had not previously been articulated.

That reanalysis became what is now known as the Stoll Curve, a foundational model in acceleration physiology that continues to be cited in aerospace medicine literature today.

Why She Rode the Centrifuge

Alice Stoll did not ride the centrifuge to generate the data behind the Stoll Curve.

She rode it because she wanted to experience it.

When she asked to ride, she was initially refused on the basis of gender. According to Stoll, she was told it would be dangerous for a woman. The reasoning was cultural, not scientific.

Stoll found and cited a U.S. government research guideline stating that investigators conducting human research must be willing to undergo the same procedures as their study subjects. The intent of the guideline was ethical, encouraging researchers to think carefully before exposing others to risk.

Presented with this policy, the researchers relented.

Stoll rode the centrifuge. She tolerated the acceleration without incident and did not lose consciousness. Her ride demonstrated that the assumptions limiting women’s participation were unsupported.

Importantly, Stoll later stated that her ride stimulated interest among researchers in formally evaluating women under acceleration. It helped initiate further studies into female tolerance of high G environments.

What Often Gets Overlooked

Alice Stoll’s work on Nomex and her contribution to acceleration physiology were separate, parallel achievements. One did not cause the other.

What unites them is not machinery, but method.

She analyzed existing data differently. She questioned assumptions. She insisted on ethical consistency. She applied rigorous measurement to problems that others treated as limits of nature.

She retired from the Navy after a long career, lived into her nineties, and remained intellectually sharp to the end. Her contributions were recognized professionally, but rarely publicly.

Why This Story Matters

As human spaceflight moves toward longer missions and harsher environments, the questions Alice Stoll addressed remain fundamental. How does the human body respond to extreme conditions? How do materials, physics, and physiology intersect to keep people alive?

Many of those answers were not born in Houston or Florida.

They were forged quietly in places like Warminster, by scientists whose names rarely appear in headlines.

Continuing the Story

Alice Stoll’s story is one of many explored in the documentary Before the Moon, which examines the overlooked people, places, and research that made human spaceflight possible long before rockets left the ground.

Learn more at BeforeTheMoonFilm.com

Follow the project for ongoing research and discoveries

Support preservation efforts connected to the Johnsville Centrifuge and its history

Some of the most important advances in spaceflight never left Earth.

Leave a Reply