Before Silicon Valley became synonymous with American innovation, there was a different kind of creative energy radiating from a quiet base in Warminster, Pennsylvania. Inside its hangars and labs, engineers, scientists, and technicians were redefining the limits of aviation, communication, and computing.

One of them was Doug Crompton—a radio engineer, inventor, and ham radio enthusiast who spent decades inside the Naval Air Development Center (NADC), later the Naval Air Warfare Center (NAWC). His story isn’t just about machines and magnetics—it’s about community, ingenuity, and the shared purpose that made Warminster a place like no other.

From Ham Radios to the Navy’s “Radio Central”

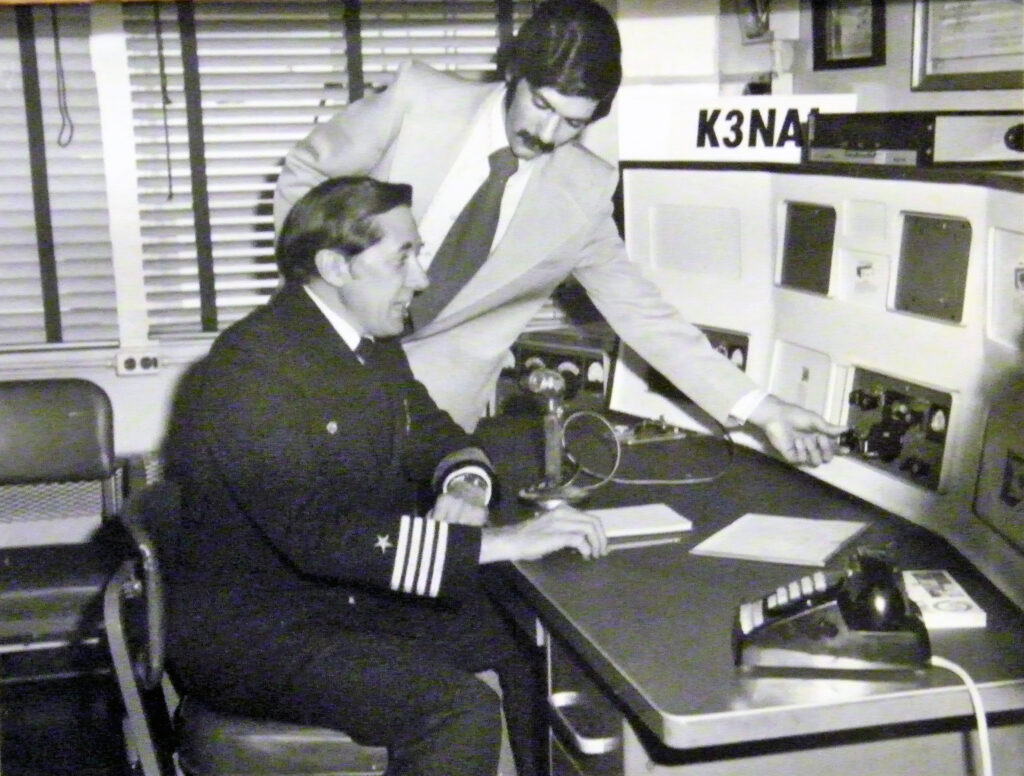

“When I came to the base, there was this massive beam antenna on the roof—it looked like a gigantic TV antenna,” Crompton recalled. “That was Radio Central. It was our communication hub. Any research group at NADC could use it to talk to field teams out on aircraft or testing ranges. We had HF and UHF radios, and we could reach across the country.”

For a lifelong ham radio operator like Doug, it was a dream job. “It was heaven,” he laughed. “I had a budget, I bought new Collins equipment—it was state-of-the-art at the time. I wish I had pictures of it. It was beautiful.”

Radio Central became the invisible thread that stitched the NADC’s projects together, from electronics testing to aircraft navigation experiments. “It was like our own internal party line,” he said. “We could talk directly to our teams in the field—real-time, engineer to engineer.”

Engineering, Film, and the Pre-Internet Era

Crompton’s technical range extended far beyond radios. “We had a full television studio at NADC,” he said. “It was called the Presentation and Information Division. They produced internal films, training videos, and promotional reels for project sponsors. Remember—this was before PowerPoint or the internet. If you wanted to make a presentation, you did it on camera.”

He became a key collaborator in that studio, helping with lighting, sound, and equipment maintenance. “Some of the cameras were huge and required careful alignment. It wasn’t plug-and-play—you had to know your craft,” he said.

Crompton even pitched a visionary idea that would make the base one of the most connected in the country. “We had a program where employees could submit suggestions to improve operations,” he said. “I proposed installing a cable system across the base so every building could access internal TV—and eventually data. It got approved, and I got a $2,000 check for it.”

Decades later, that very system was adapted for early internet networking. “They used it as the backbone for the local area network,” he said. “That was late ’70s, early ’80s—pretty futuristic for the time.”

From Test Equipment to Magnetic Memory

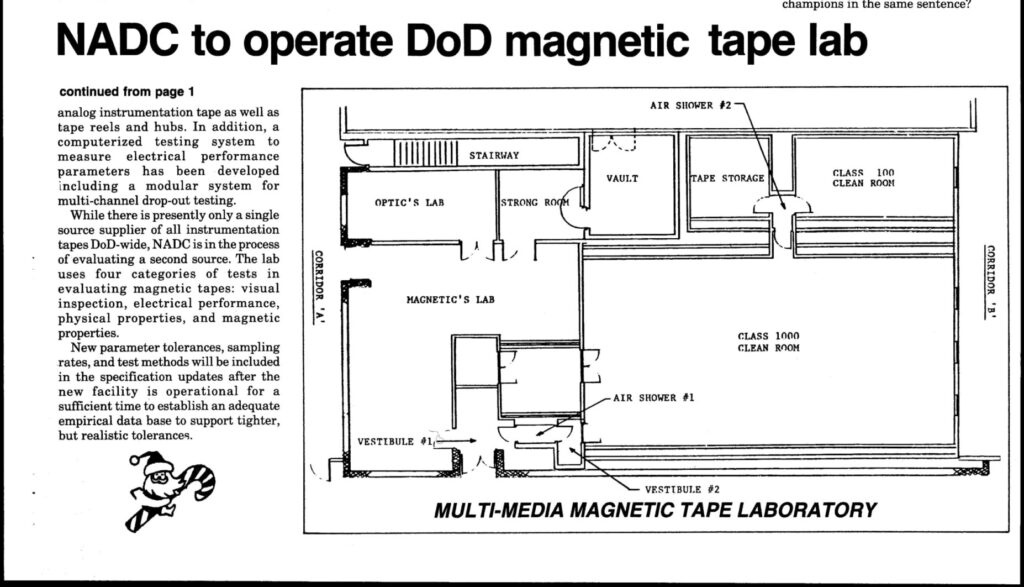

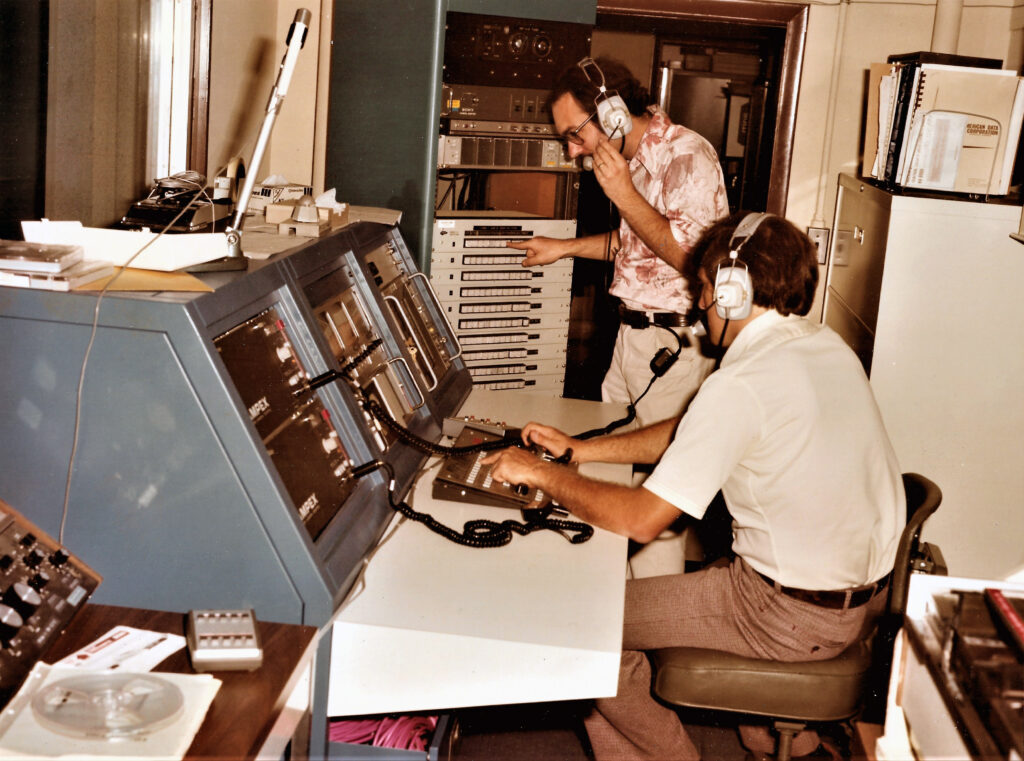

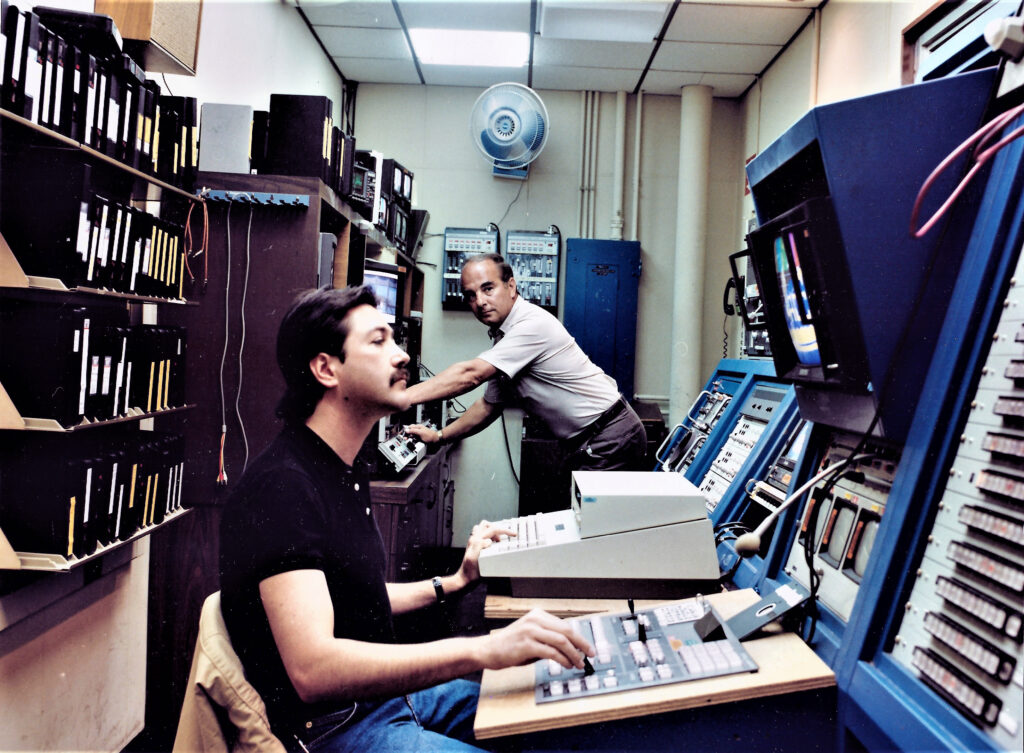

As NADC evolved, so did Crompton’s work. “I started in the test and calibration division,” he said. “But later I joined the Information Storage Branch. We were doing cutting-edge research on magnetic tape, optical discs, and early CD technology.”

One of his most fascinating assignments came under physicist Dr. Richard Joseph, a specialist in magnetics from Sperry Univac. “We built a lab from scratch—millions of dollars of test equipment,” Crompton said. “We were researching bubble memory, which was non-volatile and radiation-proof—ideal for aircraft and space applications.”

Bubble memory stored data in magnetic particles that could “float” within a sealed medium. “It was crude by today’s standards,” he said. “Tiny capacity, but revolutionary for its time. The goal was to make memory that could survive vibration, shock, and radiation.”

That work extended into vibrating sample magnetometers and digital signal processing—projects that merged the worlds of physics and computer engineering long before those disciplines officially overlapped.

From Researcher to Entrepreneur

Crompton’s story didn’t end with the lab. A casual conversation with Dr. Joseph would soon change both their lives. “We had a visitor from the West Coast who said, ‘What the world needs is a way to test magnetic hard drives without destroying them,’” Crompton said.

That idea sparked a company: Innovative Instrumentation, Inc. “We started in his garage,” Crompton said. “It was the classic startup story. I built the electronics in my basement, and we made instruments that tested magnetic materials non-destructively. We sold to IBM, Seagate, 3M—mostly on the West Coast and in Japan.”

The company thrived for 22 years. “It was the right idea at the right time,” he said. “We built seven or eight products, made a lot of money, and sold all over the world. Most of our units ended up in Asia, especially Japan and Malaysia.”

When the recession hit in the mid-2000s and hard drive technology shifted, they closed the company on their own terms. “We were lucky,” Crompton said. “We saw the change coming and got out gracefully.”

Archiving a Legacy

When the Warminster base closed in 1996, Crompton stayed until the end. “It was heartbreaking,” he admitted. “People lost their jobs, their community. For me, it wasn’t about money—it was about losing something special.”

But he couldn’t let that history disappear. “They were throwing everything away—photos, documents, reports,” he said. “They’d put boxes in the hallway, and I’d go through them every day, saving whatever I could.”

Those rescues became the foundation of what’s now the NADC Historical Archive, preserving the memory of a facility that trained astronauts, tested flight systems, and powered Cold War research.

“It’s not just about nostalgia,” he said. “It’s about making sure people know what happened here. Because what we did in Warminster changed aviation, spaceflight, and even computer technology. People need to know that.”

The Spirit of Community

For all the high-tech innovation, Crompton’s fondest memories are human. “We had open houses where the public could walk through the hangars, meet the engineers, see the centrifuge spin. Kids would sit in cockpits. It was magical,” he said.

He also chaired the base’s welfare and recreation committee. “We organized Christmas shows, hot air balloon launches, Corvette shows, even fun runs,” he said. “It was a family. Everyone knew everyone. The Christmas programs were elaborate—skits, choirs, full lighting setups. We filled two shows every year.”

Those events, he said, reflected the same ingenuity that defined their work. “We didn’t just build machines—we built memories. We built a community.”

The Closing and the Continuation

When the base officially shut down, employees watched as the Naval Air Warfare Center lettering came down from the front gate. “Underneath it, carved in stone, was the word Brewster—the original company that started it all,” Crompton said. “That was poetic. A full circle.”

Today, Crompton continues to manage the NADC Alumni website, connecting hundreds of former employees. “We keep each other’s memories alive,” he said. “That’s what matters most.”

Support the Film

Help us tell the stories of space pioneers and innovators like Doug Crompton.

• Visit BeforeTheMoonFilm.com

• Support the film through our donation page

• Follow us on Facebook: facebook.com/BeforeTheMoonFilm

Because before we go forward… we need to remember who got us here

Leave a Reply